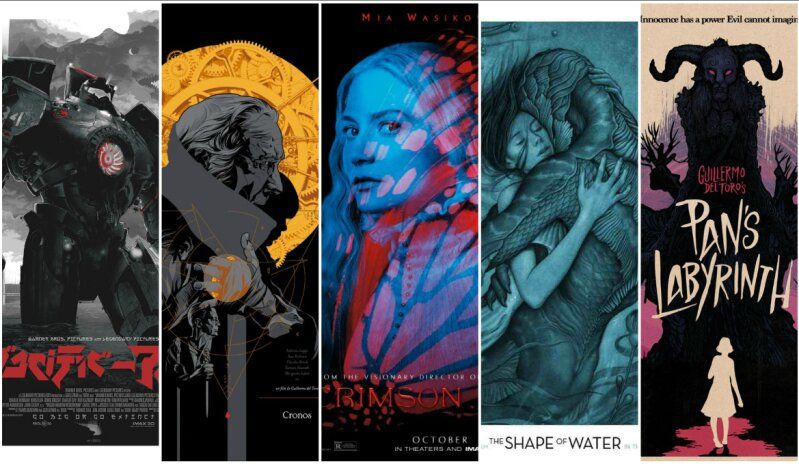

The master of anarchic Tales: Guillermo del Toro

This week Filmustage will delve into the wonderful fairytale worlds of Guillermo del Toro. We will try to highlight the main features of the Mexican master's directorial style.

Hollywood storyteller Guillermo del Toro - a true aesthete and fanboy with a broad outlook. His childhood left wounds on his soul, but helped him to form a distinctive worldview and a unique directorial style. Del Toro's work proves that cinema can be simultaneously entertaining, intellectual and beautiful. That's why today we want to take a closer look at the director's features of the Mexican master.

Disclaimer: our blog has no academic purpose behind it, because we are viewers just like you. Filmustage does not aim to educate, but to gather a close-knit film community around us. We can be wrong about certain statements - and that is fine. We are open to discussion and criticism. The main thing is to love cinema and talk about it.

Before we continue, we want to remind you that here we promote the love of art and try to inspire you to take your camera and make a short film. Leave the boring pre-production routine to the Filmustage - automatic script breakdown - and focus on your creativity!

Also after a long time of hard work we are happy to announce the beta-testing of the new Custom categories feature in the Filmustage software. Be one of the first to test the new functionality - click here for more detailed information.

Art by @nadi_bulochka

How the real horror turned into the horror on the screen

Most of del Toro's pictures are filled with fear and pain. In "The Devil's Backbone" (2001), for example, the soul of the dead cannot find peace; the heroine in "Pan's Labyrinth" (2006) escapes into a dream world from her fascist stepfather; and the demon's stern son, "Hellboy" (2004), actually appears as a self-ironic do-gooder who worries about his dual nature. Certainly the key to this perception of the world is to be found in the director's past.

Guillermo grew up in the Mexican city of Guadalajara. This region is characterized by a phenomenon of religious syncretism: Catholicism mixed with Aztec mythology, which gave Christianity a new and macabre quality. Bloody versions of biblical parables terrified the boy from a religious family.

Guillermo's grandmother, an orthodox Catholic, played a large role in his upbringing, instilling her conservative views in the child by telling him about purgatory, original sin, and eternal torment after death.

Del Toro's biggest shock was the kidnapping of his father by the Mexican Mafia. It happened in 1997, when the director was working on "Mimic" (1997), his debut film in the States. He enlisted the help of a close friend and colleague, James Cameron, who hired a professional negotiator and helped pay the ransom. When his father was released, del Toro moved his family to the United States.

After his experiences, evil has become for him the same integral part of the world as good. And Guillermo del Toro does not draw a clear line between them, but believes that opposites complement each other, like yin and yang. Thus, deprivation gives a bitter but useful experience, hardens you and teaches you to appreciate what you have.

This understanding of the indivisibility of good and evil is reflected in del Toro's work. He believes it is unfair to show only light or darkness - and always strives for balance. That is why the director is so fond of dark fairy tales, whose characters, like himself, overcome fear and pain, make sacrifices, but in the end become better or change the world around them.

Perfection is to be imperfect.

Del Toro's style is an intellectual fantasy in which religion, history, politics and philosophy meet with elements of fairytales and horror. Complex ideas are juxtaposed with simple and understandable for the mass viewer motifs and images.

For example, "The Shape of Water" (2017) is, at first glance, a sentimental love story. Nevertheless, del Toro singles it out as the most reflective of the director's inner world, because Guillermo del Toro denounces racism, sexism, and xenophobia through the love story.

Thus, the film conveys the idea that people are all different and that despite our differences there is always room for love. Therefore, in del Toro's fabulous world, the purest and most sincere love is between an amphibian man and a mute girl.

The focus on the aesthetics of imperfection also underlines the fact that an important place in del Toro's work is occupied by monsters, on which the director pays fanatical attention to detail, while working on them.

Each feature has to characterize the creature: its experiences, its physiology or symbolism. For example, the horns of the elf ruler in "Hellboy II: The Golden Army" (2008) are a natural symbol of power, emphasizing his legitimate right to the throne. And the usurper prince can only rule with an artificial crown.

In del Toro's films, the monsters do not exist by themselves. They are visually and narratively connected to their surroundings. For example, the ghosts of the women in "Crimson Peak" (2015) are the same bloody color as the clay in which they are buried. And the faun's horns reflect the shape of the maze where he lives, so the creature is literally associated with nature.

To better integrate his creatures into the narrative, del Toro makes them change with what is happening. For example, the closer the full moon and the more tests the heroine performs, the more powerful and younger the faun looks. And the amphibian man luminesces when he is overwhelmed with feelings.

As a child with a passion for drawing and biology, and later for many years worked as a makeup artist, the director himself develops the design. It all starts in his notebooks filled with drawings and detailed descriptions of monsters. The director then passes his concepts on to a team of artists who make edits and bring the designs to life.

Del Toro entrusts the most important monsters to Doug Jones, an actor who specializes in non-human roles. On his account: faun, amphibian man, hand-eyed monster and other creatures of the director.

Once as a child, del Toro watched the classic horror film "Frankenstein" (1931), directed by James Whale. The monster, condemned to death by its creator, looked like a martyr, like Jesus in the child's imagination. The monster reminded the child of his own imperfection, but at the same time, the boy noticed a certain supernatural grandeur in him. To Guillermo, the monster was beautiful in its own way.

"My hole dogma and cosmology of Catholicism fills with a monsters of the movies. I found empathy and I found beauty in the monsters, I found them patron saints of imperfection and the patron saints of all earnest and I truly became the cipher by which I could phrase the world...", – Guillermo del Toro's interview to the Los Angeles Times.

Thus, a combination occurred in del Toro's mind, only this time Christianity was combined not with myths, but with monsters. Del Toro began to see them as saints who embody otherness, suffer and die for it.

The director likes to repeat that monsters saved his life. They influenced his worldview and creativity. Del Toro's ability to see the beautiful in strange and non-ideal things allows him to tell even the most exotic stories with extraordinary sincerity.

Most vividly del Toro expressed his love for imperfection in "The Shape of Water". The film is like the fairy tale "Beauty and the Beast", only turned inside out. "Beauty" in it is far from Hollywood standards, and her beloved river monster doesn't become a prince at the end.

The water that surrounds them is used by the director as a metaphor for love. No matter how imperfect and different people may be – true love, like water, takes the right shape to iron out all differences and imperfections. Having fallen in love, the characters remain themselves and accept each other as real.

Tale in reverse

Guillermo Del Toro's films do not just defend otherness, but also criticize a society obsessed with ideals, standards and order. According to the director, the fairy tale is a very politicized genre that is well suited for such purposes.

The director divides fairy tales into pro-systemic and anarchic.

The former impose the current order and call anything that does not conform to standards evil. Kings are fair and wise, princes are handsome and noble, and monsters are bloodthirsty and cruel - but nothing else.

Such praise of order is alien to del Toro. Even as a child, he suffered from his grandmother and the church, then as an immigrant fought against the states and, finally, as a filmmaker defended his ideas to the studios. After all that, he became completely disillusioned with social institutions.

Therefore, the tales that del Toro tells are anarchic in nature. They undermine the current order and show that the system itself, for all its outward appeal, can be a real evil inside. The moral of his tales is simple: don't blindly obey the rules.

If his favorite heroes are outsiders and fringe characters, the villains in his films are usually forces that maniacally strive for perfection, superiority and control. These include the Nazis in "Hellboy", the oppressive parents in "Crimson Peak", and the American militarists in "The Shape of Water".

The author's hatred of the system peaks in "Faun's Labyrinth". In this tale, the director uses disobedience as a leitmotif. The heroine resists her naive mother, the mysterious faun, and finally the fascist Captain Vidal, the system's main evil. Each time the plot rewards the girl's defiance.

Remarkably, at first del Toro evokes sympathy for the villain. The captain has a well-groomed appearance and impeccable manners, which, however, soon come into contrast with his inhuman cruelty. The rotten gut of Vidal and fascism in general is symbolized by a faceless monster devouring innocent children.

Afterword

We sincerely believe that the worlds of Guillermo del Toro are impossible to fully understand, but to touch and try to explore the experiences and pain the Mexican director put into his films. Guillermo del Toro is a recognized master of cinematography, which he uses not only to narrate his mystical tales, but also to tell the stories of those who all along have remained unheard. That's why we appreciate the cinema that del Toro creates.

What do you think? Thanks for being with us and see you next week!

From Breakdown to Budget in Clicks

Save time, cut costs, and let Filmustage’s AI handle the heavy lifting — all in a single day.