On the border between film and music: Damien Chazelle

What is the price of a dream? We believe director Damien Chazelle will help us find the mark.

Have you ever drawn an analogy between film and music? The question may seem silly, especially since cinema is a visual art, but we have a lot to share in this regard. Perhaps you should take a look at the work of Damien Chazelle because there is no more musical director who is so precisely and sensitively able to synchronize melody and image. And we're not talking about the simple juxtaposition of music that is in every film - we're talking about something more sensual and aesthetic. It is in this twisted synergy that lies the amazing style of Damien Chazelle, which we want to talk about in our new blog!

Disclaimer: our blog has no academic purpose behind it, because we are viewers just like you. Filmustage does not aim to educate, but to gather a close-knit film community around us. We can be wrong about certain statements - and that is fine. We are open to discussion and criticism. The main thing is to love cinema and talk about it.

Each director has a different idea of how the script will look on the screen. That's why being able to create the image of your film in pre-production is extremely important. Visualise how you see all the elements in your script with Filmustage's Visual Reference board.

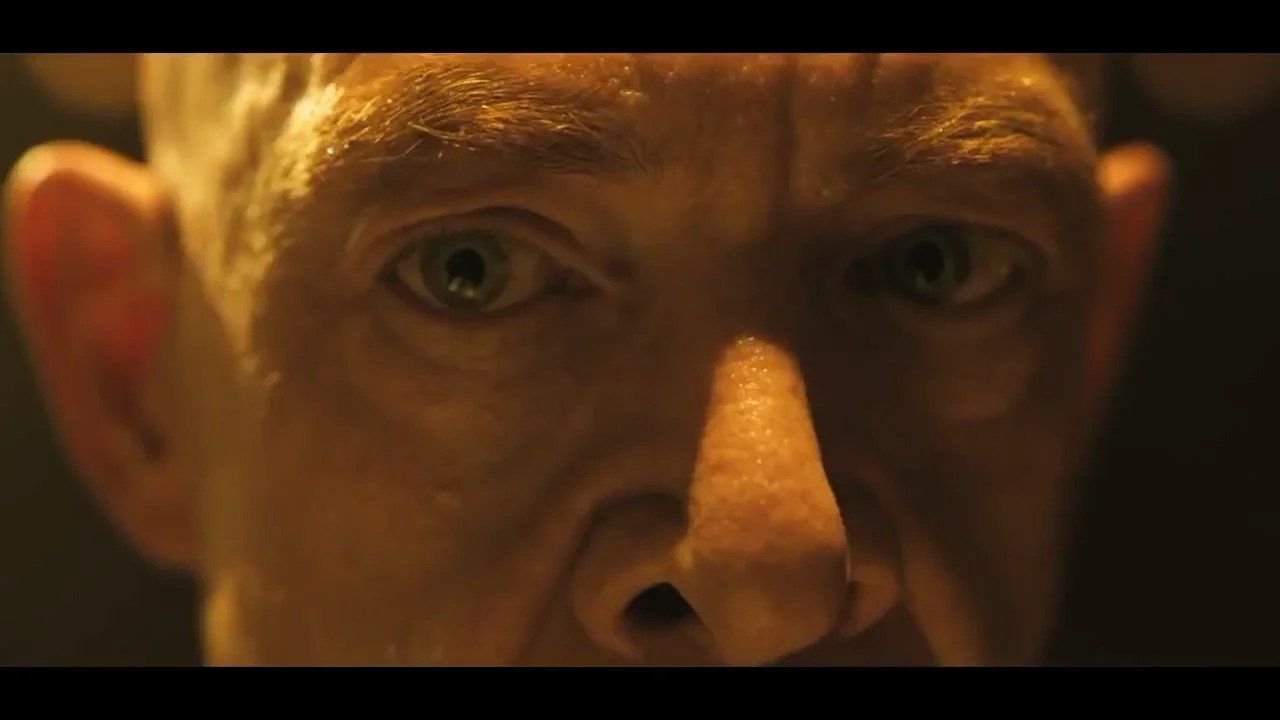

Art by @nadi_bulochka

From music to cinema, or how to turn melody into an image

Damien Chazelle was born in Providence, Rhode Island. His mother is a writer and history professor at The College of New Jersey. His father is now a renowned computer scientist. Chazelle always wanted to be a filmmaker, inspired by "Full Metal Jacket" (1987), "The Umbrellas of Cherbourg" (1964), and "That Thing You Do!" (1996). In high school, however, he went in a completely different direction and became a drummer in Princeton High's school band. That experience, however, was not useless for his film career and left a deep mark on his future screenplays.

"My overall emotion during those years was just fear," he recalled. "My teacher scared the hell out of me. He would scream and curse and insult people, or would kick musicians out of the band. Even the looks he would give us, and the constant starting and stopping or searching out people who were out of tune. I remember literally having to play just this one downbeat over and over again for about 20 minutes in front of the entire band. ... And when I saw 'Full Metal Jacket', I thought, 'My God, someone put my band experience on film. "

The process of drumming was more of a compulsion than a hobby for Damien. He practiced six to eight hours a day in his parent’s basement, inflicting permanent red abrasions on his hands, desperate to please the director's frantic demands.

As a result, Chazelle was able to quit the band, claiming that he, unlike the protagonist of "Whiplash" (2012), had no talent, but the young man felt he could make it in Hollywood. Chazelle enrolled at Harvard Film School, from which he graduated in 2007. The result of his studies was a black and white film about an unhappy love affair, “Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench” (2009), which cost a modest $50,000.

The warm reception from critics allowed Chazelle to settle in Hollywood, with the result that his scripts began to gain more and more popularity. For example, the young director managed to work on scripts for “Grand Piano” (2012) and “10 Cloverfield Lane” (2016).

Finally, he took it upon himself to remake his old script about his years in a jazz band. Titled it "Whiplash" (2012) and finished it in 10 days. Jason Reitman, director of "Juno" (2007) and "Up in the Air" (2009), read the script and decided to invest in a movie. However, before Chazelle started looking for money for the production Reitman advised him to first make a short film based on one of the scenes from the full script. So, after some time of hesitation, Chazelle did just that.

Everything worked out well: together with J.K. Simmons and young actor Johnny Simmons, the film easily won the jury prize at the 2013 Sundance Festival. Soon after, Bold Films decided to invest in the film - which is how the now iconic "Whiplash" came about, bringing the creators many nominations for prestigious awards as well as worldwide recognition.

Emotional swing. Or is it?

There is a characteristic emotionality to Chazelle's cinematography that might be confused with trivializing the viewer's emotions. In our view, however, this directorial principle works in a completely different way - and that is what sets Chazelle apart as a good screenwriter and director. Nothing in his scripts is set in an external environment - all the events and emotions experienced within the film are an integral part of the characters. Through the conflict, the characters go from beginning to end, but it is characteristic of this author's directing that neither the viewer nor the hero knows how the climax will unfold until it happens.

Life is not predictable. Life is not fair and following one's dreams and hard work does not always lead to the desired outcome. We are so used to romanticized images from Hollywood that, like a conveyor belt, bring us happy ending after another. Chazelle's commentary on this subject is that the audience in the cinema should not know how the protagonists’ fate will turn out - they have to live through, get into the role of these characters: be puzzled, pondered, and made up their minds. Chazelle doesn't just bring all the logical chains to a climax, but makes it the high point of the film, after which the viewer is left with no questions: did the hero do the right thing?

After studying each of the director's films, you can come to the simple conclusion that at the heart of each of them is an uncomplicated story. Whether it's the story of a loser striving to become a jazz star or a romantic love story where ambition comes between feelings. Bet, you've seen a movie that meets one of these narratives more than once. That's why we obviously may expect a happy ending from the finale of "Whiplash", and why we expect Mia and Sebastian (the heroes of "La La Land") to be able to be together.

The viewer naturally wants to see the resolution of all conflicts, but no Chazelle film satisfies this requirement, since this director's climaxes are reduced to dramatic uncertainty. Let's take an example: in "Whiplash" there is an obvious conflict between Andrew and Fletcher, and we spend the entire film waiting for Andrew to show all the possibilities and finally earn recognition for his skill. But as soon as the moment arrives, which should be a triumph for the protagonist, Fletcher once again crushes him right in front of the audience. What predictability can we talk about when Chazelle boldly destroys the developing conflict between the two characters, literally referring to the very genesis of the confrontation between the two characters!? But, as they say, one step back, two steps forward.

Precisely the same way all expectations are shattered in "La La Land", where the emotional conflict of the characters should lead to the long-awaited reunion, but Chazelle puts a fat end to it right before the finale.

In other films, most audiences would have been disappointed in this kind of ending long ago, but Chazelle's films only gain more tension from the emotional context: Andrew is still broken after an hour and a half of running time, and Mia and Sebastian are not together. Chazelle's climax is an explosion, a music video, and a bright, proper conclusion.

It is safe to say that Chazelle has a talent for creating several climaxes in one film cause in both "La La Land" and "Whiplash" we are still given a happy option. For example, "La La Land" depicts characters in love who achieve their goals together and are happy. After the hurricane and the suspense, Chazelle gives us what a lot of people wanted.

Once again, we are fooled. Moments of happiness and triumph do not last long as nothing is perfect in this world. And in this again we can see the wicked irony of life, which Chazelle emphasizes. In "La La Land", Sebastian is slowly replaced by another lover of Mia's until they find themselves together with a child. That's it. They will never be together again - and both characters realize it.

In "Whiplash", the moment of euphoria ends along with a gradual slowing of the pace. When Fletcher, with a frantic stare, erects the tempo again, the audience, like the hero, is brought back to reality.

In this way, it is as if Chazelle is colliding the present and the desired, where the latter simply cannot exist. These contradictory feelings are reflected not only on the characters but also on us, the audience, helping to finally formulate and answer the question: What is the price of a dream?

A little bit about music

As we have already said, Chazelle is able to turn entire segments of his films into music videos. The point, however, is that he completely subordinates the image to the rhythm, creating scenes that are guided by the type of music from beginning to end.

The simple truth is that the music in Chazelle's films seems to be thought out before anything else. It's not just an accompaniment to the image - it's part of the script, part of the dialogue between the characters, which sometimes reveals more about them than any line. Note exactly how Chazelle ends his films: in his first three works, the finale is accompanied by a silent but musical ending, with music acting as language. For Andrew and Fletcher, jazz becomes the language of art, deprivation, and pain; for Mia and Sebastian, it is an opportunity to fantasize about love. But there is also, of course, a commonality: two silent close-ups that speak the language of dreams.

Damien Chazelle uses simple techniques to create some of the most exciting and suspenseful scenes in cinematography. Because of his musical background, and his emphasis on music even in pre-production, his films are music in pictures. It's so authentic that the final scenes from both "Whiplash" and "La La Land" will make you sit with goosebumps, just like after listening to your favorite piece of music.

Visual Style and Techniques

In this block, we would like to draw attention to such an extremely interesting technique as the whip-pan and the way Chazelle masterfully uses it in his films.

Whip-pan is a sudden movement of the camera from one object to another during which the image is blurred. In essence, it is a classic panorama, but very fast. Usually, whip-pan is used in dynamic transitions between scenes, to show several events in a short period of time to enhance the effect of the action of the character, to accelerate the movement, or to convey violent feelings: passion between the characters, heroic flight, fear of the threat.

Damien Chazelle pushes the boundaries by using whip-pan more often than most directors: he deliberately complicates scenes and uses the device for various purposes. He is obviously a very musical director, always focused on the music, and has a finer sense of it than many of his colleagues. So Chazelle's whip-pan stems from the sound of the soundtrack.

In his debut film, "Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench", there's a moment where one guy plays the trumpet and the other dances. Chazelle was thus combining a complex space so that it was impossible to badly show one character through the other. Here it creates a concrete effect of presence as if we were standing in a jazz club: we'd have fun looking first at the trumpet player, then at the dancer, and so on, too.

In "Whiplash" this is done very coolly, at the expense of the musicianship. The visuals adjust to the music.

In the first part of the film, when the main character meets the conductor, the technique works to dramatically show the change of state in the scene. In the introduction scene, the hero sits and plays. J.K. Simmons' character reacts caustically to this and leaves, then comes back and says, "I forgot my jacket." We needed to show how quickly the decision was made-just like a whiplash. That's why you need that kind of sudden movement.

We think there are two reasons for the scene. The first is to create crazy speed, and the second is not to tear up the scene with the montage. Because editing is, after all, some language that crushes the scene.

The second point is the unexpectedness of the decision. It's the suddenness of him leaving that's important. Chazelle made the effect so strong because the conductor rejected the drummer's double-swing.

Afterword

Chazelle's films leave you speechless. He has shown how beautiful and sincere a different language than ordinary words can be. For that we would like to thank him. In his relatively short career he has already been able to produce some classic films, in our opinion. So we are looking forward to his future projects, because we are sure they will remind us once again how to dream.

From Breakdown to Budget in Clicks

Save time, cut costs, and let Filmustage’s AI handle the heavy lifting — all in a single day.