How illusions are created: Christopher Nolan

Nolan is an extremely versatile filmmaker, and his films are a very skillful bridge between two global branches of cinema, namely between the auteur and the commercial. Today, we will try to dissect the director's style and answer the question, how does Christopher Nolan create magic on the screen?

It's fair to say that Christopher Nolan is a living legend. In a career spanning 25 years, he has directed 17 films, all of which are noteworthy. Nolan is an extremely versatile filmmaker, and his films are a very skillful bridge between two global branches of cinema, namely between the auteur and the commercial cinematography. Christopher Nolan is not just a director, but a magician! His films deceive and confuse the viewer, but they also mesmerise them: it's almost impossible to take your eyes off his films. So today, we will try to breakdown the director's style and answer the question, how does Christopher Nolan create magic on the screen?

But before we continue, we want to remind you that here we promote the love of art and try to inspire you to take your camera and make a short film. Leave the boring pre-production routine to the Filmustage - automatic script breakdown - and focus on your creativity!

Also after a long time of hard work we are happy to announce the beta-testing of the new Custom categories feature in the Filmustage software. Be one of the first to test the new functionality - click here for more detailed information.

Art by @nadi_bulochka

Re-directing the fabula

To get you started with Nolan's work, it's worth talking about two classic cinematic terms: plot and fabula.

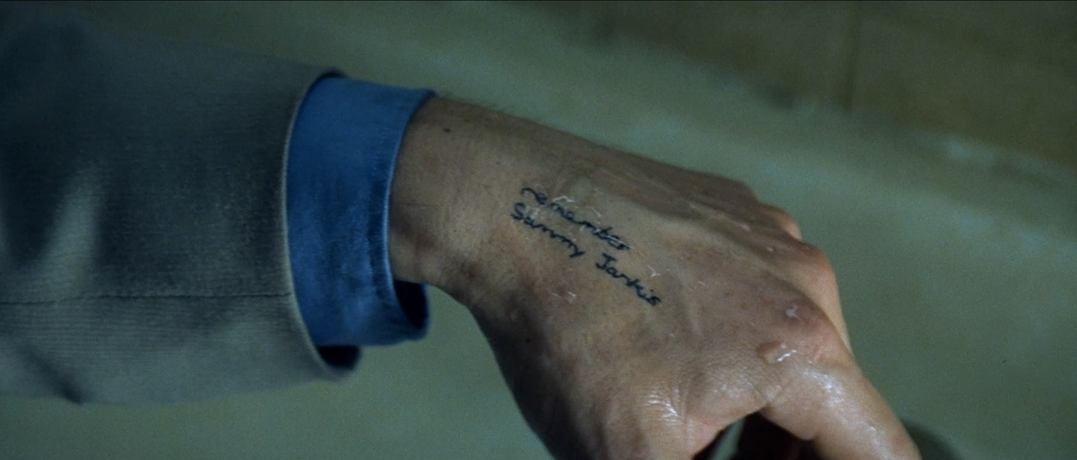

The fabula represents the overall content of the work: the world, its setting and the characters. Namely, it is the context in which the film unfolds. So the nature of the fabula could be described as completely linear and self-explanatory: all events occur chronologically and the characters act sequentially. Nolan's method is to break down the fabula, at first, and then turn the linear story upside down. This is why, for Nolan, the fabula is not at all equal to the final image of the film, as can be seen in his first major project: "Memento" (2000).

In "Memento", a story could be developed into a coherent narrative. But then, according to Nolan himself, the film would become a simple thriller and, most importantly, would not represent the very idea of the "Memento": create the most realistic representation of anterograde amnesia in cinematography.

In "Memento", for example, events unfold around a culminating moment - the finale - in which two lines combine: the past and the future. The climax represents the only episode of the present flow of time in the film, as the past and the future are woven into a non-linear thread. The past, i.e. the episodes leading up to the climax, are seen by the audience in black and white. On the level of visual style, flashbacks are shot in a less emotional but objective language: long-shots that emphasise the isolation of the protagonist, as well as a general restraint in camera movement and composition. Flash-forwards, in contrast, i.e. events after the climax, unfold in colour and present the audience with a subjective view: hand-held camera, lots of action and dialogue.

Non-linear editing

Certainly this is why one of Nolan's major structuring techniques is the principle of non-linear editing, which involves a huge number time jumps. In "Memento", the entire composition aims to immerse the viewer in the protagonist's disease: anterograde amnesia. That's why the film contains almost the greatest number of time jumps in cinematic history. The viewer, along with the character, is forced to remember what his goal is and what he meets.

With non-linear editing, Christopher Nolan produces his complex plots, such as the past and the future being combined into the present in the "Memento" finale.

Nolan's cinematography is thus a complex labyrinth in which he places his characters. And for all the blockbuster nature of his films, Nolan stays true to the human being and explores the human mind through his films with genuine interest: memory, dreams and time. Ultimately, the viewer, only has to watch as they tangle between illusion and reality.

Christopher Nolan, along with his screenwriter and brother Jonathan Nolan, have forever changed cinema by showing that audiences can be interested in complex and convoluted films.

Loyalty to realism

In a way, Nolan remains an old-school director, as his filmmaking techniques keep the use of computer graphics in movies to a minimum. If you have to blow it up, you blow it up for real. Perhaps one notable example is the hospital bombing in "The Dark Knight": the film crew actually used an abandoned chocolate factory that cost over $100,000 to build.

Or talk about another iconic moment from "Inception", for which the crew built a giant centrifuge the length of a hotel corridor, and Joseph Gordon-Levitt trained for weeks to reproduce the scene.

Special effects and tightly rehearsed stunts give Nolan's films a unique seriousness and realism which, with "Batman Begins", has forever changed not just the way blockbusters are seen but also the way comic book movies are seen.

Nolan's films, on the other hand, are known for their interesting and unique computer effects which do not contradict, but only underline the director's passion for realism and verisimilitude. In addition to "Memento", "Insomnia" and "Inception" being noted as the films with the most faithful depiction of human memory, insomnia and dreams in cinema, even during the pre-production stages of "Interstellar" Christopher and his brother Jonathan collaborated with Nobel laureate Kip Thorne to get the scientific basis for each of the director's artistic findings. The result of their collaboration was a CGI construction of a black hole, which was a revelation for visual effects in cinema.

Visual style

We think it's silly to argue that the visuals in Nolan's films look simply stunning. His films just look different from everyone else's. Why? The answer is very simple: the film. The director has been synonymous with film since his first movie and has no intention of changing his philosophy. His movies are made either on 35- or 70-mm film, the main advantage of which is the image quality. And despite the abandonment of VistaVision and Super Panavision 70 in the 60s and 80s, Christopher Nolan is one of the few who have remained faithful to analogue film production. It is because of the high resolution and quality of the film that his movies, even on a visual level, appear to be very large scale. This is especially evident in the shots from the 70mm film, which can capture very wide expanses.

Separate attention should be given to post-production, which until recently was also done in analogue format, without the film being digitised. Also colour grading, which is not done by computer, but by special developer techniques.

Collaboration with cinematographers

It's very interesting to talk about technology, of course, but it means nothing without the person who operates it. So it's time to talk about who is responsible for the stunning angles and composition in Nolan's films.

Wally Pfister is a close friend and collaborator of Christopher Nolan who has worked on every one of his films, from "Memento" to "The Dark Knight Rises". Wally Pfister won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography for his work on "Inception" in 2011.

Masterful in light techniques, Wally Pfister manages to pull off what is probably one of the most cinematic shots ever. His close-up shots are very expressive and full of emotion, while his wide compositions make you want to admire the picture instead of looking at it. It was Wally Pfister who was one of the first to adapt the bulky, heavy and incredibly expensive IMAX cameras for feature film. That's why you'll rarely see a handheld camera in Nolan and Pfister's joint portfolio - it rarely appears as a necessary visual-dramatic accent.

Another cinematographer, Hoyte Van Hoytema, replaced Pfister, who left to build his directorial career. Together with Christopher Nolan, he has begun work on a major project entitled "Interstellar". Against the measured style of Wally Pfister, the Swiss cinematographer managed to adapt the huge IMAX camera for handheld shooting, which allowed him to shoulder the camera and shoot the most unimaginable shots. Hoyte Van Hoytema's camerawork style is nothing short of cinematic poetry, which we have already written a separate blog about (click here).

Afterword

Christopher Nolan combines many qualities, but one thing we can say for sure is that he is a director who believes in the magic of filmmaking and diligently produces it. His ardent love of cinema as an art form is evidenced by both his willingness to shoot on film, his obsession with practical effects and analogue practices, and most importantly, his stories. His subjects could unfold into a major conflict, but at the centre will still be the individual and his choices. So for all the spectacularity of Interstellar, for example, we still want to cry in the finale.

Watch movies, love movies. See you next week!

From Breakdown to Budget in Clicks

Save time, cut costs, and let Filmustage’s AI handle the heavy lifting — all in a single day.