The frightening chameleon or how to get to know Lars von Trier

No one likes to be manipulated, but that's exactly how Lars von Trier's pictures feel. Today we will try to answer the question of why love-hate relationships have developed around this director.

There is much hatred for this director for his contrived and excessive frankness. Others find him on the verge of political correctness and sincerity. We don't want to take sides, but we take this challenge. What kind of director is Lars von Trier, and how to approach his movies? Today we want to dedicate our blog to the most controversial filmmaker of our time.

The master of trilogies.

Cinephiles and people not indifferent to the world of cinema have long identified three areas in the works of Trier, which can be easily grouped into a few distinctive periods, corresponding to the development of the director as a person. Therefore, it is only worth comparing the styles of the early and late periods - and we find that we are as if we are dealing with several different directors.

Europa trilogy ("The Element of Crime", "Epidemic", "Europa")

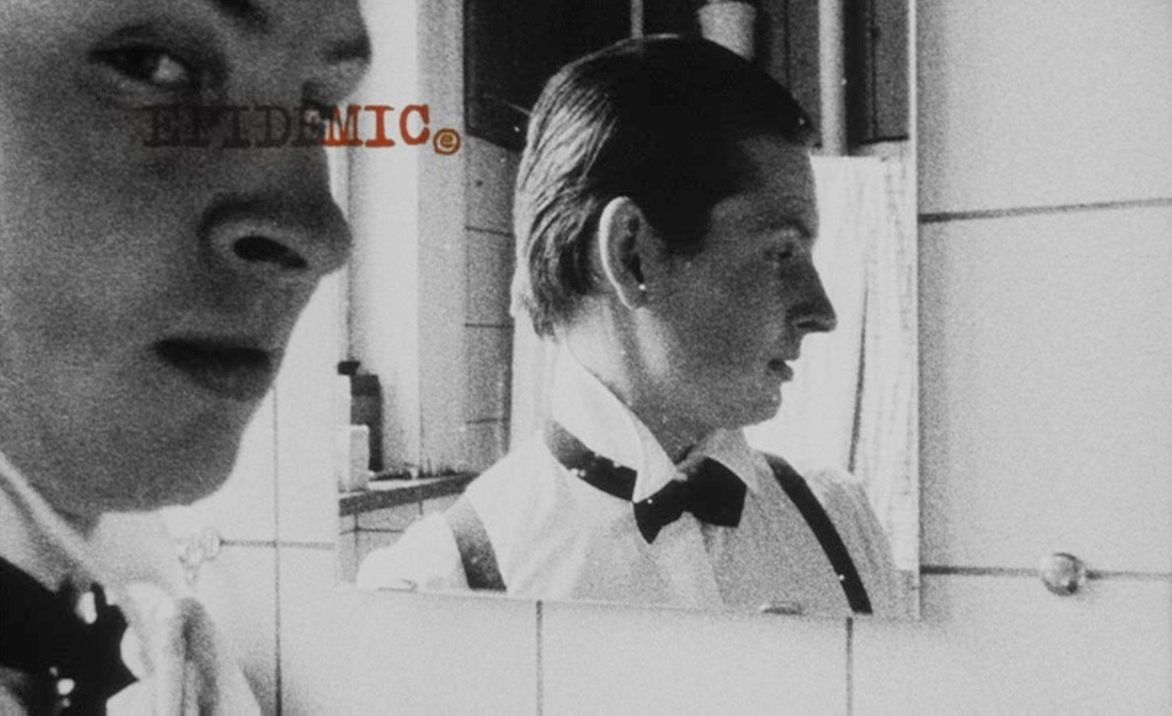

Lars von Trier has not been shy about appearing on either side of the screen in his earlier works: he often performed as an actor in his films. It is how he and his characters roam through a dreamlike Europe full of longing and darkness.

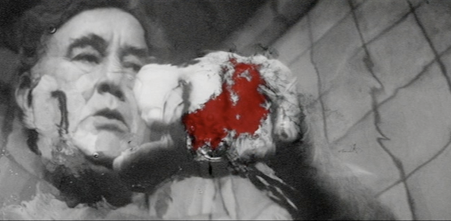

The subjects of Trier's first films often succumbed to a visual range that could by no means be called meager: complex camera movements, the slo-mo aesthetics, double exposures, experiments with scales, and color.

Shots from the "Europa" (1991)

Using variable visual techniques, the director dissects the trauma and pain of the past to look into the future with interest. Lars von Trier's first projects show how highbrow the director set himself at first, and he was very good at it. However, in favor of a visual aesthetic, Trier had already begun to deconstruct the genres and forms we are accustomed to, which is reflected in the second chapter of his art.

The Golden Heart Trilogy ("Breaking the Waves", "The Idiots", "Dancer in the Dark")

In the mid-'90s, things were changing drastically. Trier was tired of writing pictures with elusive content, so he radically changed his style. First, this shift is noticeable on the visual level, as the director decided not to restrain his emotions by the frames of static shots anymore. Trier's camera felt as if it had been freed from its shackles. The handheld camerawork and the deliberate carelessness are introduced in the documentary's visual language and the action's spontaneity. For example, you can spot the director's reflection in one of the shots in "The Idiots" (1998) or a microphone accidentally caught in the frame.

As you can see, there is no trace of the perfectionist maniacally controlling every movement. Secondly, the changes are felt at the level of screenplays. Finally, in Trier's characters, you see actual people who think and act. The dramatic and torn picture keeps the audience riveted to the screens and forces them to follow the protagonists' fates. In addition, Trier allowed the actors to improvise, coming up with entire dialogues right during the shooting.

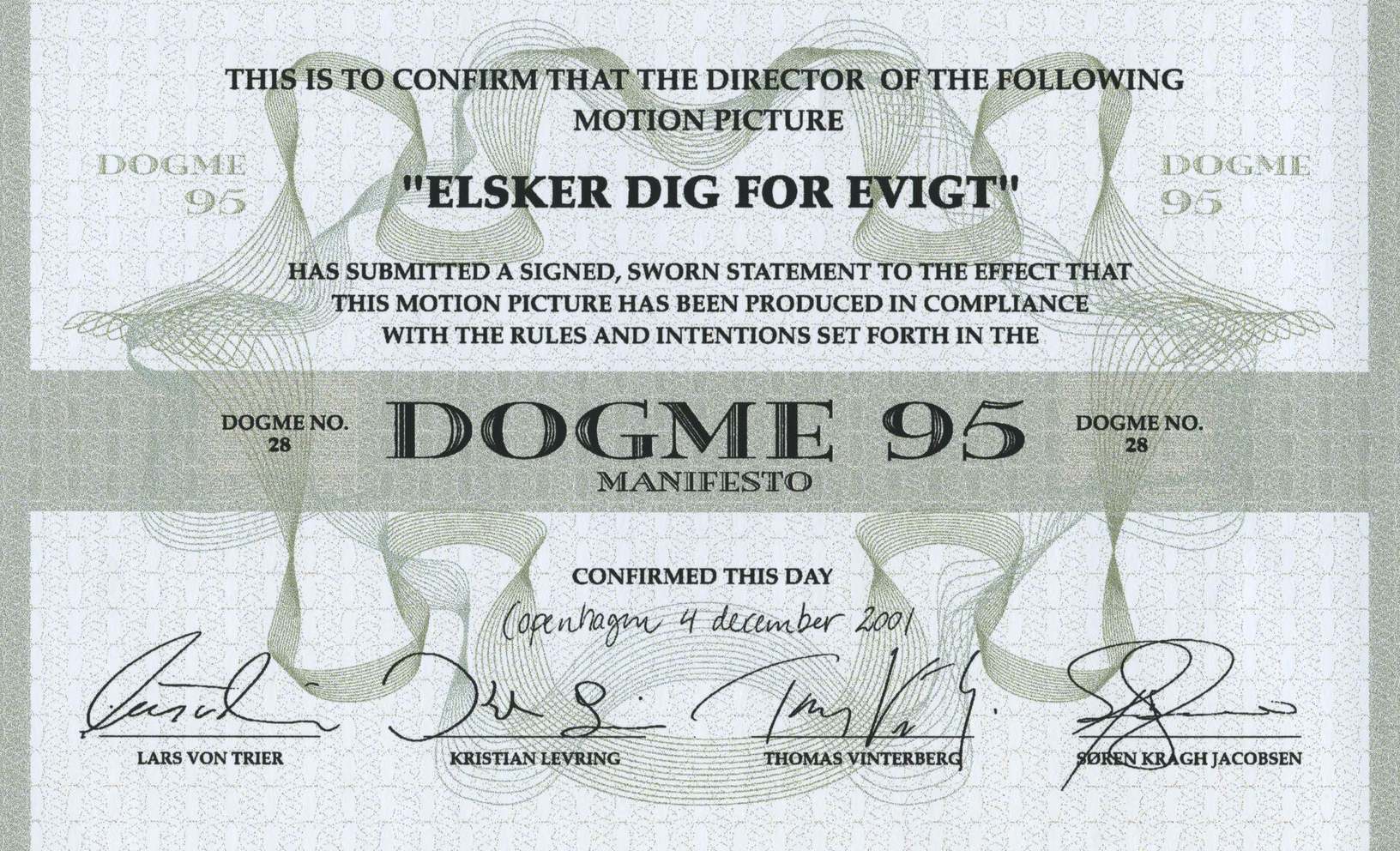

Then, Lars von Trier founded the Dogme 95 movement to defeat illusion on the screen and deconstruct our understanding of cinema. Other prominent filmmakers, including Thomas Vinterberg (director of "The Celebration," 1998, and "Another Round," 2020), were among the co-founders of the movement.

The Land of Opportunity Dilogy ("Dogville", "Manderlay")

This period concludes two films, "Dogville" (2003) and "Manderlay" (2005), as well as one unrealized project. Lars von Trier is known to suffer from aerophobia, but that didn't stop him from trying to recreate the spirit of America.

Trier tried to recreate the screen America with chalk, placing inscriptions on the hangar floor and inviting viewers to imagine building walls on their own. It is how the film "Dogville" emerged, which, in comparison with the director's previous works, went even further in the field of experimentation.

The director makes it possible to imagine a dog named Moses, a cozy woodland with birdsong, and so on. It is as if they are trying to convince us that we are watching a theatrical production. Still, the shaky camerawork allows us to immerse ourselves in the cinematic story head-on.

Despite the director's general provocativeness during this period, much criticism poured out on the author for his ambiguous portrayal of racism and sexism. Nevertheless, by speaking out on a particular subject, he was trying to reveal universal truths about human nature.

By abandoning conventional storytelling techniques, Lars von Trier proved that the mere label of "dog" could evoke the same emotions as a real animal, provided there are good actors and first-rate dramaturgy.

The Depression period ("Antichrist", "Melancholia", "Nymphomaniac Vol. I-II", "The House That Jack Built")

The following four films are set in modern times when the director was diagnosed with clinical depression. While trying to cope with his illness, Trier simultaneously guided his characters and us, the audience, through the suffering.

Since then, every film by Trier has stood out for the unsettling diagnoses of his protagonists. Kirsten Dunst's character still has the same clinical depression in "Melancholia" (2011). The heroine of "Nymphomaniac" (2013) suffers from an irresistible sexual attraction. In "The House That Jack Built" (2018), Jack suffers from obsessive-compulsive disorder.

This phase of the director's work combines all of his previous experiences, and in these films, the hand-held camera is juxtaposed with a sterile image that looks more like video art than film.

Strange as it may seem, the depression has opened the way to any experiments: paintings, chronicles, drawings, and even animation began to appear in the Danish director's cinematography - and Lars von Trier found the use for everything.

Struggling with predictability

Since the founding of Dogme 95, Lars von Trier has made it his mission to destroy viewer stereotypes. So he declared war on dramaturgy, calling it predictable. That's why one of the most striking features of Trier's films is their shocking denouements, which are particularly striking against a background of the unhurried narrative.

Lars von Trier's style is unbearable - he's so good at pulling viewers out of their comfort zone. It makes you want to close your eyes and run away, but that's not all.

With unprecedented boldness, the director works with different genres, alternately giving the drama than the musical. In his filmography, you'll find what many would consider pornography, but none of them unfolds on the screen according to the accepted canons. Instead, within one genre or another, Trier either tells an unorthodox story or resorts to an aggressive style, creating a cultural symbiosis.

How does a bloody thriller about a serial killer get footage from a harmless cartoon? Trier slowly leads us into a state of mild insanity, allowing us to feel the despair of the film heroes to the maximum extent. These fragmented visuals and chaotic plot make us close to the mental instability of the characters - so we are willing to empathize even with the killer.

Citation

However, if you're wondering where Lars von Trier came from, you should turn to the classics. The most significant number of times, the Danish director referred to Tarkovsky, scrupulously repeating his most cinematic shots.

One can also see the influence of the great Ingmar Bergman, from whom the young director soon disowned without finding recognition from his idol.

A third important reference point for Lars von Trier has always been his compatriot Carl Theodor Dreyer. At the start of his career, Trier had a chance to work with Henning Bendtsen, the cameraman who shot all of Dreyer's most iconic films.

Afterword

Lars von Trier was, and still is, the chief provocateur and manipulator of modern cinema. Nevertheless, he desperately escapes the typical image of a classic director, many of whom have been stuck in their style for a long time. With each film and era, you can see, if not a revolution, an evolution in the Danish director's creative approach. He is not afraid to experiment and does not neglect cinematic methods to take the viewer out of balance. Art must evoke emotion, even if it is uncomfortable; otherwise, what is it for?

From Breakdown to Budget in Clicks

Save time, cut costs, and let Filmustage’s AI handle the heavy lifting — all in a single day.