How Star Wars changed the cinematography

In anticipation of one of the major holidays of the year, Filmustage has a new blog for you, which is, of course, dedicated to Star Wars!

In anticipation of one of the major holidays of the year, Filmustage has a new blog for you, which is, of course, dedicated to Star Wars! More than 40 years ago, George Lucas created a universe that today could be talked about for hours on end. We don't have that much time, however, we decided to tackle one thing: how exactly Star Wars changed the film industry.

Disclaimer: our blog has no academic purpose behind it, because we are viewers just like you. Filmustage does not aim to educate, but to gather a close-knit film community around us. We can be wrong about certain statements - and that is fine. We are open to discussion and criticism. The main thing is to love cinema and talk about it.

Before we continue, we want to remind you that here we promote the love of art and try to inspire you to take your camera and make a short film. Leave the boring pre-production routine to the Filmustage - automatic script breakdown - and focus on your creativity!

Also after a long time of hard work we are happy to announce the beta-testing of the new Custom categories feature in the Filmustage software. Be one of the first to test the new functionality - click here for more detailed information.

Art by @nadi_bulochka

The practical effects revolution

It's getting harder and harder to surprise us with special effects, but we give little thought to the path that the effects industry has taken in cinema. It's a long and interesting journey that deserves its own story, but it's the Star Wars franchise that holds the key to the development of special effects.

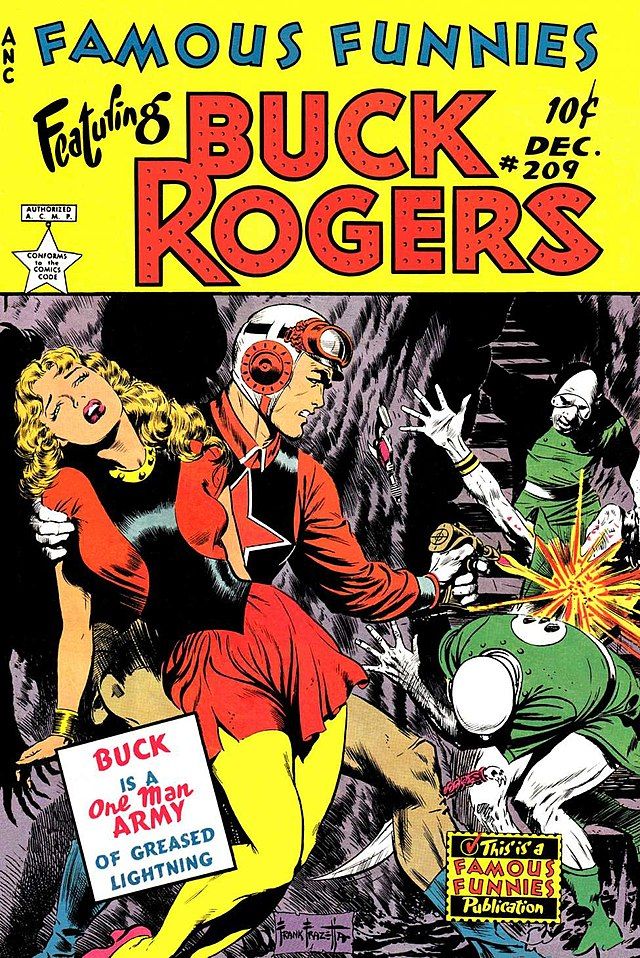

George Lucas had long envisioned a heroic space fantasy in the style of sci-fi comic books, film series and pulp-novels from the 40s and 50s. The main influence on Star Wars was space operas like the "Flash Gordon" series and the "Buck Rogers" franchise. The plot of the upcoming film, however, referred to Akira Kurosawa's mythical plots. It is with such introductions Lucas began to pitch Star Wars, but most studios rejected Lucas's concept, because the idea of a massive space opera seemed very unprofitable, and expensive to produce. Nevertheless, the director found a studio - 20th Century Fox - that put the project into production.

From the outset, this project was different from anything that existed in the sci-fi genre. George Lucas set himself the task of making a simple and understandable tale for the mass audience, which, moreover, should impress everyone visually. It was with this goal in mind that he set up the visual effects studio Industrial Light & Magic in May 1975.

In an interview, special photographic effects supervisor of the "Star Wars" John Dykstra talked about the difficulties they faced:

"Back in the days of "Star Wars", we kind of walked into an empty warehouse and sat on the floor and went: How are we going to do this!?"

The ILM team had to create not just space battles, but the most epic and spectacular ones. The main reference was a chronicle of actual aerial battles and even rumour has it that in the very first edit, which Lucas showed to his close friends Steven Spielberg and Brian De Palma, they edited excerpts from war movies instead of space battles. Nevertheless, special effects technologies that could simulate outer space have been around for a long time: they include miniature, matte painting and keying.

For example, the pinnacle of technological sci-fi could be considered "Forbidden Planet" (1956), in which director Fred M. Wilcox used every technique available, from miniatures to stop-motion animation. However, none of this has saved "Forbidden Planet" from time: the film has aged considerably. The original Star Wars trilogy, on the countrary, still looks breathtaking: space sequences are really convincing (of course, you could be a snob for a second and say that SW is also outdated, but we disagree).

In the production phase, the ILM team had two main options: 1) move the miniatures themselves to simulate movement, and 2) use keying, i.e. shooting the miniatures from different angles against a blue background to then replace it with a dynamic background. But it seems to us that these traditional ways have a number of key problems. Firstly, it would be virtually impossible to create a dynamic and engaging space battle in this way. Secondly, the image will turn out flat and boring: there is simply no volume. And thirdly, the combination of a jizzing miniature and keying looks artificial. Just look at the footage from the classic series "Star Trek" (1966-1969).

We don't want to insult the legacy of the great Star Trek saga, as it also reformed the Sci-fi genre. A large miniature moves slowly through a static shot - which in general is more reminiscent of a battle of sumbmarines than spaceships. There's just no entertainment in it, and, as we found out, George Lucas really wanted to make a massive, fun movie.

So the ILM team changed the rules of the game: instead of moving the miniatures in front of the camera, they decided to move the camera around the smaller models. In this way, the camera around the model simulated flight and action. In fact, specifically for "Star Wars" John Dykstra invented first digital motion control camera system, controlled by giant computers from the 70s, which at the time could take up an entire room! This system was called Dykstraflex (funny, isn't it?) and was capable of controlling every axis of camera movement with incredible precision. With the invention of motion control, filmmakers were able to repeat the take over and over again, as each scenario of camera movement could be programmed. Additionally, the precision of the Dykstraflex allowed certain scenes to be broken down into elements: first the camera circles around a static miniature; the next take adds movement to the miniature itself as well as effects; then the same take continues, only with the Death Star's surface. Then, piece by piece, the scene was assembled using an optical printer.

It's worth noting that Stanley Kubrick used motion control in "2001: A Space Odyssey" back in 1968, but the technology developed by John Dykstra and the ILM team was a revolution. Not only did they win a well-deserved Oscar, but they also introduced a new trend: motion control has caught Hollywood's eye.

Prequels and spin-offs

If George Lucas is to be believed, he was ready to start the prequels almost immediately after completing the original trilogy, but he was stopped by the fact that the existing technology didn't meet the director's requirements, so the projects had to be frozen. Star Wars returned in the late 90s - and it was a blast.

The idea for the prequel trilogy was to show the galaxy in its heyday, at the height of technology and civilization - and on that contrast to tell the dramatic story of the fall of the hero and the old system. It was impossible to do without small sets here, as Lucas wanted to show new planets, races and also to turn the tale into a political thriller. Did he succeed in it? We think you can answer this question yourself.

Lucas chose to work with Computer Generated Image (CGI) to realise his grand plans. As controversial as these films were, you have to admit that the Star Wars prequels were the first films to create huge worlds in CGI. It takes a lot of confidence and a touch of madness, doesn't it? And Lucas has done it: he's gone from insanely bad first episode to "Star Wars: Episode III - Revenge of the Sith", which has given us one of the most spectacular and dramatic duels in cinematic history.

A new trilogy conceived by Lucas would revolutionise and deconstruct the way films used to be made. The set is now a room furnished with blue screens, and the actors are forced to rearrange their work because many of the characters they play with never existed: they are entirely computer-modelled characters.

It would not, however, be fair to say that Lucas has completely neglected his own legacy, namely practical effects. This is not the case, and there is an excellent video on You Tube on the subject.

Afterword

Innovations has always accompanied the Star Wars franchise. At every stage of its development (let's forget about the last trilogy), these films have given the cinematic world a new impetus that we can still see in every blockbuster to this day. One can argue about the artistic value of the prequels, but the cultural and technological contribution of Star Wars cannot be underestimated. Certainly credit must be given to George Lucas, John Dykstra and the great Industrial Light & Magic team who pioneered the revolution. And now that George Lucas has long since stepped away from his brainchild, Star Wars continues to expand, with spin-offs: "The Mandalorian" and "The Book of Boba Fett" has already become iconic post-westerns, which introduced the revolutionary Virtual Production technology! However, it's another side of the Star Wars legacy that we've tried to explore in one of our recent blogs (click here).

On this day we would also like to congratulate and thank our friend Roger Christian, producer, director and production designer. Roger Christian has, over the years, worked on numerous cult productions, among them Ridley Scott's "Alien" (1979), as well as George Lucas' "Star Wars" (1977) originals, for which he received an honorary Academy Award. Roger Christian has always been at the forefront of technology and contemporary solutions, which he applies in practice in his work on his documantary "Galaxy built on hope".

Congratulations to ourselves and all fans: use the promocode MAYTHE4THBEWITHYOU and get 20% discount.

From Breakdown to Budget in Clicks

Save time, cut costs, and let Filmustage’s AI handle the heavy lifting — all in a single day.