Diving into the past with Robert Zemeckis

Today we will talk about the fascinating figure of director Robert Zemeckis and try to understand why he is so attracted to the events and personalities of the past.

Robert Zemeckis is a director with a rather interesting fate. He entered the big cinema stage as the author of major films and gave the world several iconic pictures filled with deep reflections on the past and future. Zemeckis does not claim the laurels of an auteur indie film, but he and other visionaries of technology were not afraid to radically experiment with the forms of cinematography. So, we are happy to present a new blog about how Robert Zemeckis has made time the central theme of his career and taught the world to travel through it with the help of stars and cars.

First Steps

Who knows, if it weren't for John Lennon and Beatlemania, Robert Zemeckis might not have become a filmmaker. The first help from the Beatles' music came when, in the early '70s, he decided to go to film school at the University of Southern California, where he submitted a short film based on the song "Golden Slumbers." There he met Bob Gale, the future co-writer of the "Back to the Future" trilogy. The two friends' tastes helped them bond, and they separated from the other students in the group. Zemeckis recalled that he and Gale, unlike the others, were never fans of the French New Wave and didn't want to make art films like European films. They were into James Bond movies, Walt Disney and Clint Eastwood and wanted to make movies in Hollywood. During his studies, the twenty-year-old filmmaker made a short work called "The Lift" (1972), a remarkable story about how a confident man's ordinary life becomes extraordinary thanks to an elevator. In the film, through insert shots of a wristwatch dial and a mechanical alarm clock, the main interest of the Zemeckis' cinematography - time - appears for the first time.

After creating a satirical short comedy about military training, "A Field of Honor" (1973), a young director won a student award at a film school. Zemeckis was noticed by Steven Spielberg, and a few years later, he helped him undertake a project called "I Wana Hold Your Hand" (1978). It mixed beloved Beatles and games with time. Set in 1964, during the height of Beatlemania in the United States, the film depicts a day in the life of American teenagers who dream of going to a televised Beatles concert. They try to race against time to get the coveted tickets before the show begins. In "I Wanna Hold Your Hand," in addition to referring to the glorious 1960s, Zemeckis' experiments with historical figures begin. He wittily hides the musicians on the TV screens of an actual performance on the Ed Sullivan Show, turns them around with their backs to the audience, and shows only small details about them by implementing POV shots. In the end, after the show, he puts the Beatles on a hearse that rushes away from the crowd of groupies, which symbolizes a wake for Beatlemania already rolled in.

Retromania and references to the past

Interest in cutting-edge technical innovations do not prevent the director from reveling in nostalgia and exploring different eras. By looking back on history, Robert Zemeckis reinforces filmmaking's properties, allowing a glimpse of a different reality. His reverent love for the past has given rise to many pop-culture personalities and allows us to call Zemeckis' cinematography an almanac of 20th-century American life.

"Forrest Gump" (1994) may have predicted the current trend of celebrities being "resurrected" for new screen appearances. It's hard to say why to go to such lengths, and it must look at least creepy (here we should think of the sinister valley effect), but now, as if by magic, you can rejuvenate seventy-year-olds or continue to use characters in a saga about a galaxy far, far away. With deep fake, for example, you can even replace Christian Bale with Tom Cruise in "American Psycho," Jack Nicholson with Jim Carrey in "The Shining," etc.

Meanwhile, in "Forrest Gump," Lennon, as the story goes, dies in 1980 and, along with it - miraculously comes back to life for a few moments at the will of Zemeckis, who, using archival footage of the musician and computer special effects, gives him a chance to meet the protagonist. However, it is impossible to prevent Mark Chapman's fatal shot. Nor is it possible to prevent JFK's assassination from happening: the smiling American president also recreated the forces of computer graphics with particular meticulousness.

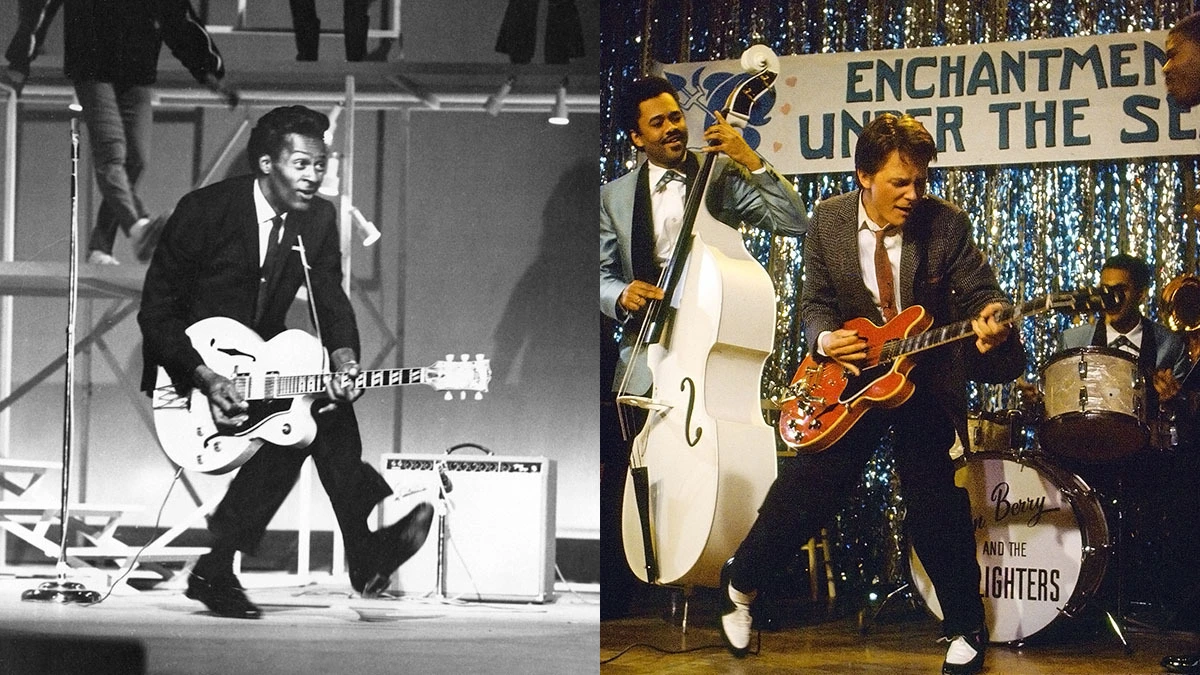

Not to forget Chuck Berry, who makes an ethereal appearance not only in "Back to the Future" but also in "Cast Away" (2000) when the Christmas hit "Run Rudolph Run" - almost like "Run, Forrest, run!" - comes out of the speakers for Tom Hanks' character. Other stars who visited Zemeckis's films include Jim Morrison, Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe, Greta Garbo, and Elvis.

Time runs its course, and Forrest has to move forward only through it, so you can, for example, instigate the Watergate scandal, but you cannot change the course of history. However, Zemeckis doesn't really want to put up with this from film to film and tries to cheat time, which he and his characters do in the second most important project - the "Back to the Future" trilogy. And at some point, the director, apparently, decided to stop the processes of human aging at all and, for the entire 2000s, went into the extremely comfortable world of motion-capture technology - a step absolutely logical if viewed in this vein.

Revolutionary Technology

Robert Zemeckis is one of Hollywood's biggest fans of technological innovations that allow for special effects. The director's interest in spectacle has been evident since his very first works. For example, "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" (1988) was the first feature film to combine feature film, animation, and CGI to such a significant extent.

The sequel to the Back to the Future franchise will long be remembered for the hoverboards and the family dinner scene where three Michael J. Foxes appear in the same shot. The director achieved this effect thanks to the then-new Vista Glide technology.

"Forrest Gump" distinguished itself with complex shots, where the director had to put the protagonist in the existing frames of the documentary. And for the labor-intensive work in "Contact" (1997), Robert Zemeckis attracted 8 computer graphics studios, thanks to which the audience at the time watched with amazement travel through the wormhole.

Zemeckis could be called the main supporter and popularizer of motion capture technology. "The Polar Express" (2004) became the first film created entirely with this technology. Additionally, it allowed Tom Hanks to perform five roles at once. Since then, Robert Zemeckis has become the biggest advocate of digital cinema, which, in his words, does not restrict the authors' freedom.

Nevertheless, after a protracted and somewhat unsuccessful experiment with motion capture, the director has continued to develop effects in traditional cinema.

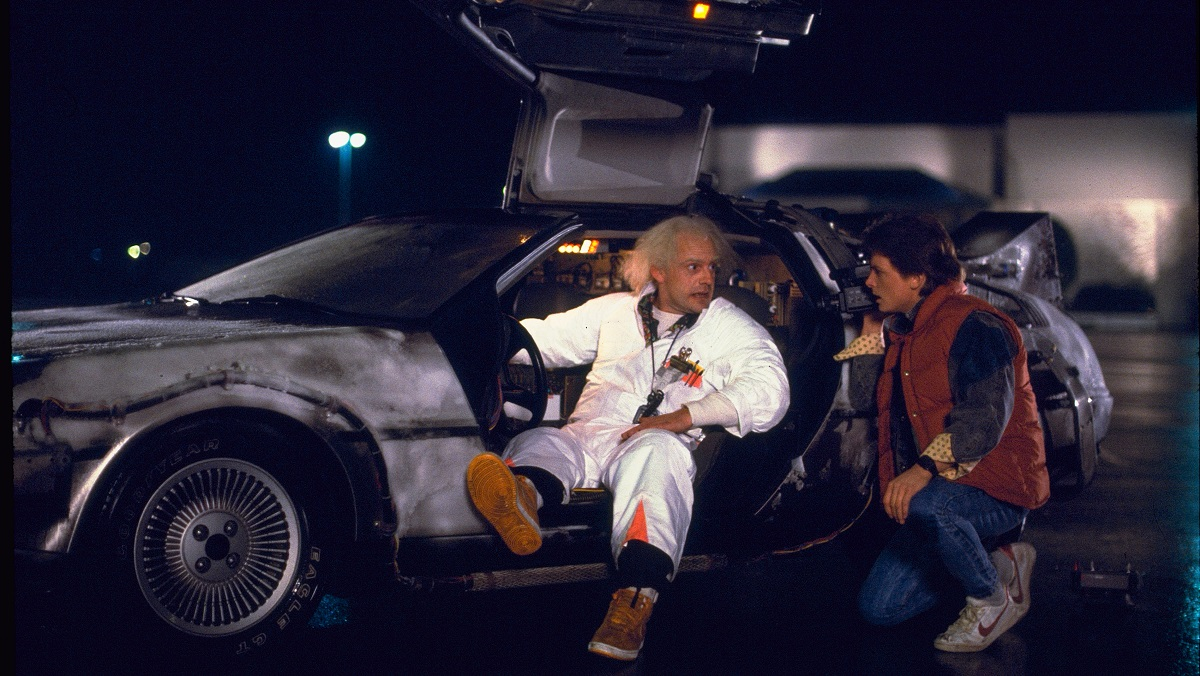

On the Road

Zemeckis loves cars almost as much as he loves watches: he often combines the two and turns the car into a symbol of time ("You built a time machine out of a DeLorean!"). Thus, his second film was called "Used Cars" (1980); it delighted critics but failed at the box office, as did "I Wanna Hold Your Hand." The title of this film, while not the most famous in Zemeckis' filmography, is nevertheless a great way to describe his recurring tricks. You might think of Benny's cartoon cab from “Who Framed Roger Rabbit” (1988), the car from "Cast Away" (2000) that Tom Hanks' character gets back after spending several years on an island, or the sunken car from "What Lies Beneath" (2000), which holds the ghost of a murdered girl. And that's not to mention the remodeled DeLorean or the stylish retro cars from "Back to the Future."

In "Forrest Gump," the role of time guide is played by the city bus that makes Forrest sit on the bench while he waits and goes back to the past. You can also think of the unlucky Porsche 550, aka the "little bastard" that Bruce Willis' character steals from James Dean in the black comedy about the elixir of youth, "Death Becomes Her" (1992).

In Zemeckis's films, time always passes in huge leaps, often eating up the mass of what happened in one short caption. This is the case, for example, with the title "four years later" in "Cast Away" or the credits "seven years later" and then "seven more years later" in "Death Becomes Her." In "Forrest Gump," as in "Back to the Future," the events of several decades pass before us as if on a green thumb, stopping on a particular era.

Visual Counterpoints

So, Robert Zemeckis is a director who gravitates toward the past. Even within the confines of one film, he can change eras. That should create incredible pacing and momentum, shouldn't it? Actually, not. Zemeckis prefers a measured visual language in the linguistically intense nature of his films. Unlike many directors, he remains a stickler for long shots. While today the average frame length is 3 seconds, in Zemeckis' filmography, it is no less than 8 seconds.

This technique is consistent with the belief that cinema is primarily a narrative art and thus requires a certain editing rhythm. A long frame shot with a smoothly moving camera allows the viewer to absorb the atmosphere of the space more deeply. In addition, for the director, it is another method of creating a spectacular: in such frames appear complex action or virtuoso choreography.

Also, long shots with Zemeckis are an unchangeable way to start a film. All of his pictures open with intricately constructed scenes, lasting from 1 to 3 minutes, allowing the viewer to fully immerse themselves in the story.

Besides this technique, it's hard to find any other distinctive features of Zemeckis' visual style because his approach to cinematography was greatly influenced by the classic and new Hollywood movies. Throughout his career in cinema, he consciously sought to create a "true" Hollywood cinema, understandable to the general audience and not burdened with contrived intellectuality.

Style by right of transmission

One way for a director to cheat time is to beat it with gimmicks, and references, to clothe it in something else, to be able to recapture the lost clock. Zemeckis has repeatedly shown himself to be a talented and sensitive stylist. "Used Cars" and "Romancing the Stone" (1984) can be considered homages to classic Hollywood comedies like those made by Howard Hawks; "Back to the Future" recalls with nostalgia the youthful 1950s and their rebels without reason; "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" and "Death Becomes Her" process canon and noir clichés, and "What Lies Beneath" plays partly in Hitchcock field.

As for "Forrest Gump," the spirit of Frank Capra, author of one of the most important American films, "It's Wonderful Life" (1942), is evident. Like Capra, Zemeckis is an optimist, a bit moralist, a lover of miracles, and a creator of the image of the American national hero, honest and straightforward. Forrest Gump clearly came from this kind of cinematography, where James Stewart and Gary Cooper played similar characters before Tom Hanks, who claimed fortitude and vitality. Someone even had the idea to edit the Forrest Gump trailer if it came out in the late forties; look it up.

Afterword

Robert Zemeckis is one of the greatest reconstructors of American history in cinema. And what makes his interest in the past remarkable is not how accurately he reproduces various facts, but how interestingly and creatively he embodies the spirit of an era. That's probably why he tries to saturate his films with as many different personalities and historical figures as possible. "Forrest Gump" will remain the best and most unbiased film in its league for many years to come. Forrest, with his mind, devoid of cynicism and organically disinclined to lie, is an unbiased symbol of time himself. There are rarely clock dials or electronic scoreboards because Forrest himself testifies to all events, he is their omen and, according to Zemeckis's version, the cause.

Making a film about American history through the eyes of an ordinary man, Zemeckis thereby took his own place in it and firmly established himself there, managing to negotiate with the endlessly running time: apparently, the director knows its secret after all.

From Breakdown to Budget in Clicks

Save time, cut costs, and let Filmustage’s AI handle the heavy lifting — all in a single day.