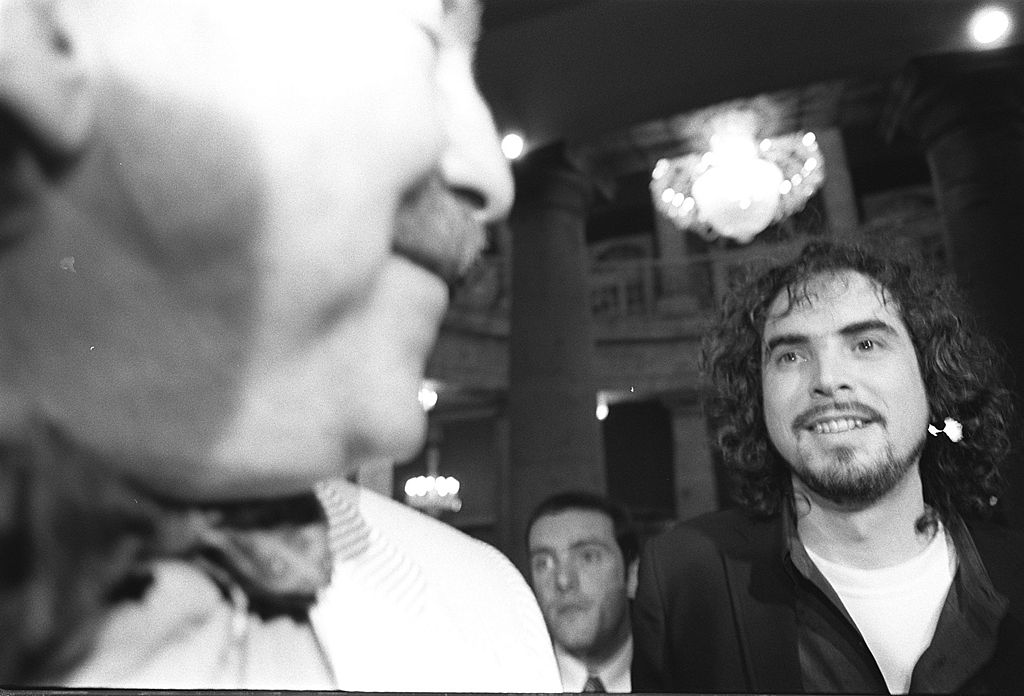

Defining truthfulness: Alfonso Cuaron

"The only reason you make a movie is not to make or set out to do a good or a bad movie, it's just to see what you learn for the next one"

Hi. What if we told you that today we wanted to tell you about the first Latin American director to receive the award for Best Director, as well as for Best Film Editing and Best Cinematography? We hope many have guessed that the hero of our blog is Alfonso Cuarón. However, all these regalia mean nothing without the works of this director, which, unlike statuettes, carry with them a rich cultural significance. Alfonso Cuarón is known as a member of the "Three Amigos", a group of revolutionary Mexican filmmakers who conquered Hollywood with their films. They include Cuarón, Alejandro G. Iñárritu and Guillermo del Toro. And since we've already talked about one of these masters in our recent blog, our work isn't over yet. Today we wanna talk about Alfonso Cuarón's directorial handwriting and answer the question of what makes his films masterpieces.

Disclaimer: our blog has no academic purpose behind it, because we are viewers just like you. Filmustage does not aim to educate, but to gather a close-knit film community around us. We can be wrong about certain statements - and that is fine. We are open to discussion and criticism. The main thing is to love cinema and talk about it.

Each director has a different idea of how the script will look on the screen. That's why being able to create the image of your film in pre-production is extremely important. Visualise how you see all the elements in your script with Filmustage's Visual Reference board.

Art by @nadi_bulochka

Biographical sketch and the beginnings of his love for filmmaking

The future director was born on November 28, 1961 in Mexico City. Alfonso is the eldest of the three sons of a physics scientist. One of his brothers became a biologist, the second, Carlos, also became a director ("Rudo and Cursi" (2008)). For a long time Cuarón himself dreamed of becoming a scientist, like his father, and then an astronaut.

However, as is often the case, his whole world turned upside down when the boy saw the world through the lens of a camera. Pretty quickly his fascination with space and science was replaced by his love of movies. His mother and grandmother were true cinephiles and constantly took young Alfonso Cuarón to the cinema after school hours. Among the films that left their imprint on the future director are "Ladri di biciclette" ("Bicycle Thieves") from 1948 by Vittorio De Sica and spaghetti westerns by Sergio Leone.

Despite the influence his mother had on Alfonso Cuarón, she insisted that her son receive a "normal education" so Cuarón studied philosophy along with filmmaking at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. However, the director now claims that the knowledge gained at the university, he did not need.

The only thing he was grateful for the film school - this is an acquaintance with his best friend, co-author and one of the most talented cinematographers of our time Emmanuel Lubetzki, which Cuaron in a friendly way calls Chivo. Together they will make most of their films.

"He's [Emmanuel Lubezki] not just a cinematographer, he's a very important collaborator. Emmanuel doesn't just set the light and frame, he's included in the narrative. While I'm writing the script, I'm always discussing it with him".

Practice was not long in coming, so immediately after university Alfonso Cuarón began working in television, acting as a screenwriter, director and editor. At this time he met another important friend, Guillermo del Toro.

The young director's big film debut was the 1991 melodramatic film "Sólo con tu pareja" in which he unprecedentedly plays with the theme of AIDS infection, giving the picture a touch of black humor. Cuarón dared to laugh at something that in the early '90s terrified everyday people. The picture was shown as part of the competition program at the festival in Toronto.

Audiences were impressed by this debut and Cuarón's name began to come across the table more and more often to American producers. So he was invited to become the director of the film "Great Expectations" (1998) based on the novel by Charles Dickens. In the process of pre-production, however, Cuarón got a script for a movie in which he immediately fell in love...

In 1995 he premiered the cult picture "A Little Princess", which the director himself considers one of the best that he had ever filmed. In the magical tale of a girl whose imagination helped her to survive the hardships that befell her, it won the hearts of viewers and really opened the director's name to the world.

The director's unique style

Visual style as a language

The fact is that Alfonso Cuarón has noted more than once that the visual aesthetic, which is certainly very characteristic of his films, is not the goal itself. He uses the visual as a language.

"If you follow something for aesthetic reasons, we have to throw it to the rubbish bin. It is a language, you know, it's not about the beauty, but about the language".

It's impossible to ignore a key feature of the Mexican director's style: long one-shot sequences. Certainly, Cuarón was not the first to skillfully use this technique. You can also see it in the works of his close friends, for example, as in Alejandro G. Iñárritu's "Birdman" (2014), where the inattentive viewer may not notice the glues at all and the film looks like a seamless canvas. However, the whole question is one of philosophy.

If you compare two masterpieces of Mexican directing: "Birdman" and "Children of men" (2006), you can say two things for sure: 1) they are visual masterpieces and 2) the same technique works differently in these films.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu tells a rather chamber-like story of an actor longing to regain his former glory. The long shots and hidden cuts help the director create a long canvas that doesn't let go of the story for a second, as if artificially lengthening it and symbolizing the long path that the character has taken. In this way the film is likened to a play.

In "Children of Men", Cuarón does not seek to disguise all the glues, because his aim is to portray the social formation of the hero, absorbed by his surroundings. In an interview on the eve of the premiere of "Children of Men", the director voiced his criticism of Hollywood cinema, arguing that these films can be watched blindfolded: that is, Hollywood tries so hard to explain the entire plot that the visual becomes only an appendage to the dialogues. However, putting the hero in context rather than the environment for the sake of the heroes defines Cuarón's manner and visual style.

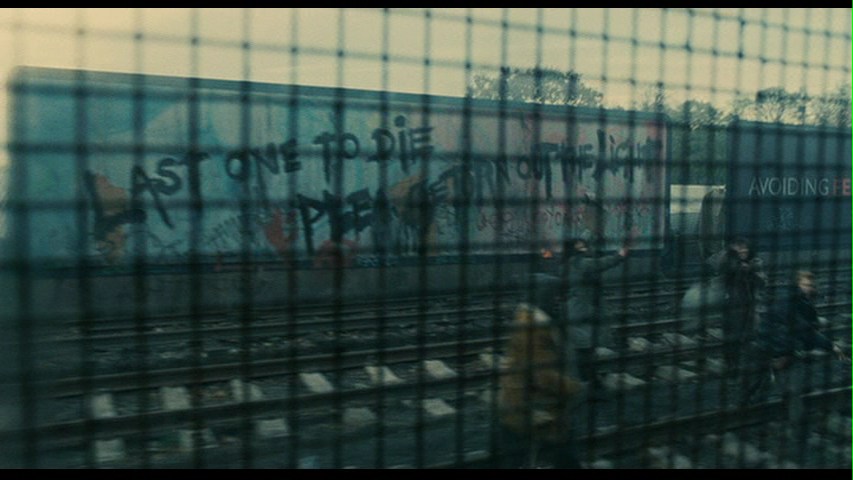

Let's return to the famous scenes from "Children of Men". Alfonso Cuarón creates a narrator in his own right who blends so seamlessly into his surroundings that he almost doesn't break it. How often have you wondered if there's a human being behind the hand-held camera in "Children of Men"?

Notice how often Cuarón's camera briefly loses sight of the protagonist to linger on the details of the surroundings: graffiti, advertisements on a train, the face of a stern security guard, etc. The camera wanders through the world of the film, capturing for us bits and pieces that reveal more and more the essence and problems of the world of the film.

Alfonso Cuarón's visual style, developed for "Children of Men", combines a unique duality: on the one hand, the camera always sticks to the characters and the viewer is able to follow their actions, while on the other hand, the camera constantly pulls away from Theo (the protagonist) to collect the image of a utopian future with details and chamber stories from newspapers, graffiti, the faces of passersby, etc. Cuarón narrates about the global through the personal.

Another example of this kind of work with visual narrative is his early work "Y tu mamá también" (2001). It explores the themes of adulthood and sexuality by depicting the story of one journey to the beach, where dreams come true.

For all its adolescent romance, the film is framed in the context of the complex domestic political situation in Mexico. Through a road trip and a handheld camera, Alfonso Cuarón shows street protests, clashes with the police and the military through the eyes of young people. Handheld photography not only displays the subjectivity of the gaze, but also the authenticity of the relationships that have developed among the protagonists: free, unencumbered by moral values and simply wanting to see the sea, young people.

Thus, Cuarón, tells two stories simultaneously: an infantile world and freedom-loving perspective collides with the harsh world of political persecution and intra-state conflicts, which leads the friends to a heartbreaking break-up in the finale.

Completely differently, long takes are used in "Roma" (2018). In this picture, everything visual is subordinate to simplicity and minimalism. You won't see the camera trying to pick out environmental details or anything like that. If in "Children of Men" the camera was a participant narrator, in "Roma" it is a narrator-observer who is not written into the environment, but as if it were part of the context. Alfonso Cuarón impersonates the camera's gaze to emphasize the loneliness and loss of the heroine, Cleo.

What Cuarón does is to make the viewer an observer from the sidelines, so it is very easy to become imbued with Cleo's story: we, just like her, are trapped. This technique is especially evident in the scene when a protesting group of nationalists burst into the store where the heroine is staying.

Just so, the Mexican master uses the visual as a language, colliding the three essential components for filmmaking: context, characters and the viewer. He doesn't just create atmosphere, but interaction between the three worlds - and that's why his films are so immersive, intense and metaphorical.

Every film is a lesson

"For me the most important thing is not the end result, but what you'll learn for the next one".

After studying Cuarón's filmography, we came to the conclusion that this director is capable of working in almost any genre. From the Harry Potter cinematic saga to science fiction. This director does not adhere to genre conventions, all because he sees each film as a challenge and an opportunity to learn something new.

Every detail is important, as we saw in the previous block of our article. Attention to detail makes Alfonso Cuarón prepare carefully for each film, thinking through every element of cinematography and acting. For example, Cuarón's thirst to learn can be seen at least in the fact that he has always collaborated very actively with Emmanuel Lubetzki on the cinematography of many projects. The director claims that Lubetzki is his constant collaborator, with whom they discuss every element of the script. As a result, Cuarón has developed a very clear understanding of the cameraman's craft and his personal visual handwriting. In fact, if you check behind the scenes from the production of "Children of Men" you can find scenes shot entirely by the hands of Alfonso Cuarón.

The result of this collaboration and constant exchange of experience is "Roma". In this very personal and, in fact, autobiographical film, Cuarón himself acted as a cinematographer, as well as an editor. Not surprisingly, this particular picture looks and feels different, although the film certainly possesses the typical stylistic techniques of the Mexican master.

Each film is a lesson. It is an opportunity to overcome challenges and learn how to make the magic of cinema more and more skillfully. This philosophy is not limited to conceptual turns, but also to purely technical ones. One has to remember the mind-blowing visual style of "Gravity" (2013), for which Cuarón and Lubetzki created a special platform with a bunch of mechanisms and cables to convey the naturalistic movements of a person in the absence of space. There was also a designed room made of panels simulating light in space (we wrote more about this in our blog dedicated to Emmanuel Lubetzki).

And what about the scene inside the car, shot in a single 360 degree take in "Children of Men"? Another director would probably have divided it into many shots, which would have violated the entire duration and immersiveness of the scene.

Alfonso Cuarón oversaw the development of a special vehicle to realize this intricate scene, resulting in giving us one of the most impressive and intense moments in cinematography.

Afterword

In fact, we don't really hope we've been able to pick up the keys to understanding Alfonso Cuarón's style. Nevertheless, we really wanted to tell you about this unique storyteller. In each film, Cuarón strives not just to tell a story, but to tell the whole world with its problems and conflicts, because only life itself, which surrounds us, gives meaning to existence. If we have been able to consider this in Alfonso Cuarón's cinematography, what can it be but art?

From Breakdown to Budget in Clicks

Save time, cut costs, and let Filmustage’s AI handle the heavy lifting — all in a single day.