Dissecting man: David Cronenberg

David Cronenberg recently recalled himself with his triumphant return to his roots. So let us devote today's material to the great and terrible Cronenberg.

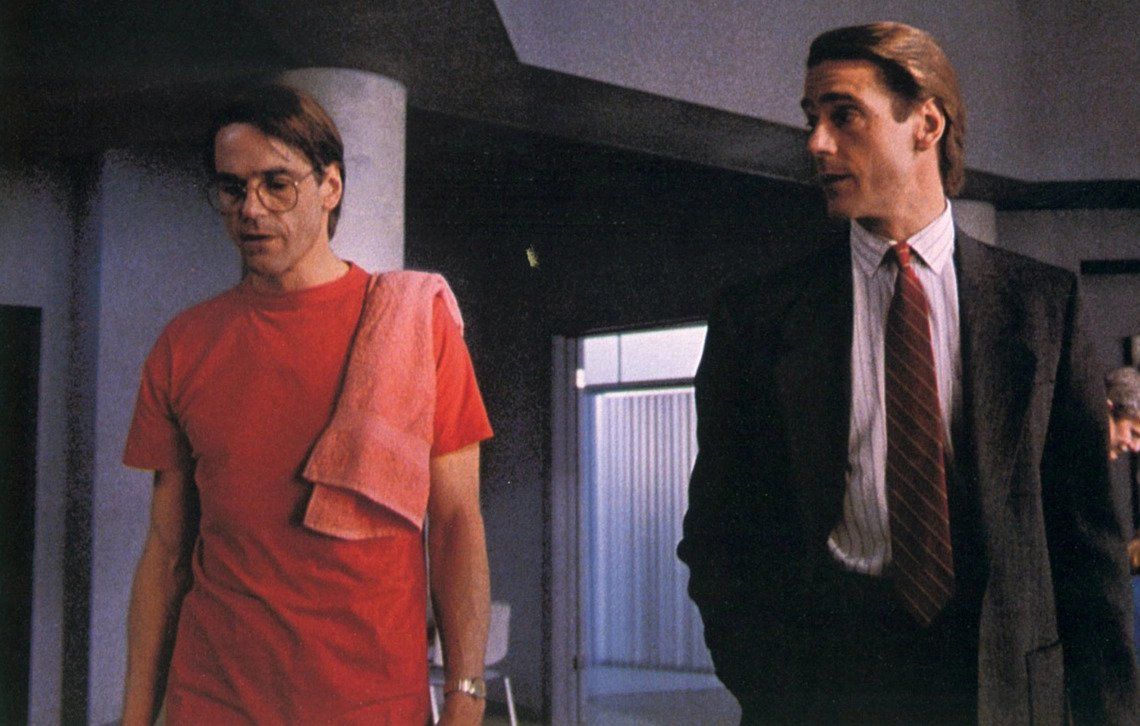

It's only recently that the 75th traditional Cannes Film Festival came to an end. Not only was it marked by the success of Japanese cinema, but also by the return of a legendary representative of American independent cinema - David Cronenberg. Cronenberg's triumph was not only that his new film “Crimes of the Future” (2022) was in the main competition, but also that the director returned ideologically to his roots and, for the first time in many years, shot a body-horror about the near future. As expected, the film was very well received: a 6-minute ovation at Cannes. So let's talk today about the style and language in which David Cronenberg creates his films.

Disclaimer: our blog has no academic purpose behind it, because we are viewers just like you. Filmustage does not aim to educate, but to gather a close-knit film community around us. We can be wrong about certain statements - and that is fine. We are open to discussion and criticism. The main thing is to love cinema and talk about it.

Each director has a different idea of how the script will look on the screen. That's why being able to create the image of your film in pre-production is extremely important. Visualise how you see all the elements in your script with Filmustage's Visual Reference board.

Art by @nadi_bulochka

Biographical sketch

David Cronenberg was born to a family of musicians and writers in 1943 and for a long time wanted to follow in his father's footsteps - to write books. At university, however, impressed by the films his buddies made, the young David decided once and for all that he wanted to devote himself to the world of film. Cronenberg studied the natural sciences, which undoubtedly affected his filmography in the future.

During his studies, the future maestro made two experimental films: "Stereo" (1969) and "Crimes of the Future" (1970). The result came out muddled, but, as with many great directors, these films should not be ignored because they are already beginning to form the basic ideas and storytelling tools of the director. Cronenberg's first commercial film, "Shivers", was released in 1975. "Videodrome", released in 1982, one of the style-making films of the decade, attracted a lot of attention.

Director's trademarks

In simple terms, David Cronenberg is considered one of the most innovative figures of the independent cinema of the 20th century. In addition, Cronenberg is the founder of the so-called biological horror genre, which means that all investigations of this trend will sooner or later lead to this very director.

Already early in his career, David Cronenberg begins to successfully ironize modern society by framing it with bizarre experiments. In his films, Cronenberg explores various psychological states of man: obsession, uncontrollable sexual attraction, aggression, rage as well as loss of connection with reality, and disocialization. The director also emphasizes his research interest in the visual component of the film: he endows his characters with strange physical mutations that develop synonymous with mental states. The finale of David Cronenberg's films is conceived as the apogee of these transformations and mutations, which dictates the great author's metaphorical message. This is why Cronenberg is commonly considered the king of body-horror and the baron of blood.

Through his work, Cronenberg tests the very notion of "norm" by giving it a relative nature. For example, one of the director's most striking techniques is to demonstrate the deconstruction of the human personality both literally and figuratively. It is a kind of self-discovery through self-destruction. In each of his works, Cronenberg tries to show what it might be like to be a man who has removed himself from the influence of the outside world.

It is for this reason that Cronenberg initially takes characters who are already at the stage of alienation because they are uncomfortable being in society. This is why Cronenberg's favorite characters are marginal people, people who have become hermits after some fundamental transformation as a result of a surgical experiment, such as in "The Fly" (1986). And since Cronenberg himself in this respect can be called an anthropologist, i.e. a scientist, his characters are also eccentric creators who are willing to do anything in order to conduct their daring experiments.

Cronenberg shows most clearly the process of deconstruction and redemption through the liberation from the natural process of sex. The almost total absence of traditional sex scenes in Cronenberg's films and the compilation of this in unconventional and even perverted ways will immediately catch the eye of the untrained viewer. Eccentric representations of sexual intercourse have followed the director from the very beginning of his career and include many variations, including the substitution of sex with virtual reality, as in "eXistenZ" (1999).

Along with various interpretations of sex, violence is a very wide field for David Cronenberg's artistic experiments, but for him, it is still a very straightforward way of communicating his thoughts, so like a surgeon he carefully replaces human body parts with metaphorical copies: the genitals, for example. In one of the director's most zanky pictures, "Videodrome" (1982), the protagonist of the picture, Max, has a hole in his stomach. In one scene, Cronenberg literally performs an act that metaphorically refers to sex.

A similar example can be found in "Rabid" (1977).

Thus, Cronenberg's characters are deprived not only of their ability to lead a normal life but also of their free will: they live and react out of base desires, which Cronenberg metaphorically likens to the act of sex. Of course, we are not saying that sex is an inferior desire. Nor do we mean to say that the hero of our blog thinks it is. However, we think that Cronenberg has deliberately chosen to eccentrically represent the impotent through the act of sex because these metaphors underline the nature of deconstruction in his films.

People in his films lose their choices for two reasons: as a result of some accident or as a result of the use of substances resembling drugs. In the first case, these are circumstances over which the characters have no control. For example, in "Shivers" (1975), parasites penetrate people's bodies, suppressing their will, and making them spread the parasites further. In "Rabid" (1977), an experimental operation causes the heroine to develop an irresistible hunger, which she can only satisfy by spreading it to other people. In "The Dead Zone" (1983), the main character gains the ability to see people's past and future as a result of a car accident and is now condemned to live for the good of others rather than himself. And there are many such examples because the people in Cronenberg's stories are all just hostages of their decisions, which turn them into puppets of uncontrollable desires.

In the second case, the human will is exercised, as I mentioned above, by drugs or their metaphors. In "Scanners" (1980), pregnant women were injected with a special substance which resulted in the birth of children guided by their supernatural powers. And in "Naked Lunch", for example, the characters take a cockroach remedy as a drug to achieve satisfaction. And finally, in the cult "The Fly" (1986), it is alcohol addiction (like a drug) that leads the protagonist to decide to conduct a fateful experiment. After complete deconstruction, David Cronenberg's characters often face an unhappy ending.

Visual Language Features

In this block, we've focused on exactly how Cronenberg portrays deconstruction. Certainly, we've all heard about the crazy effects, costumes, makeup, and animatronics that appeared in most the director's films. And when asked what you associate with the director's visual style, many will answer mutants and monsters. And that's not surprising at all, because that's what Cronenberg puts at the forefront. In our opinion, he does it deliberately in order to distract the viewer from the artful visual storytelling. We would, however, like to tell you a little bit about another aspect of David Cronenberg's visual language: his work with lines and composition.

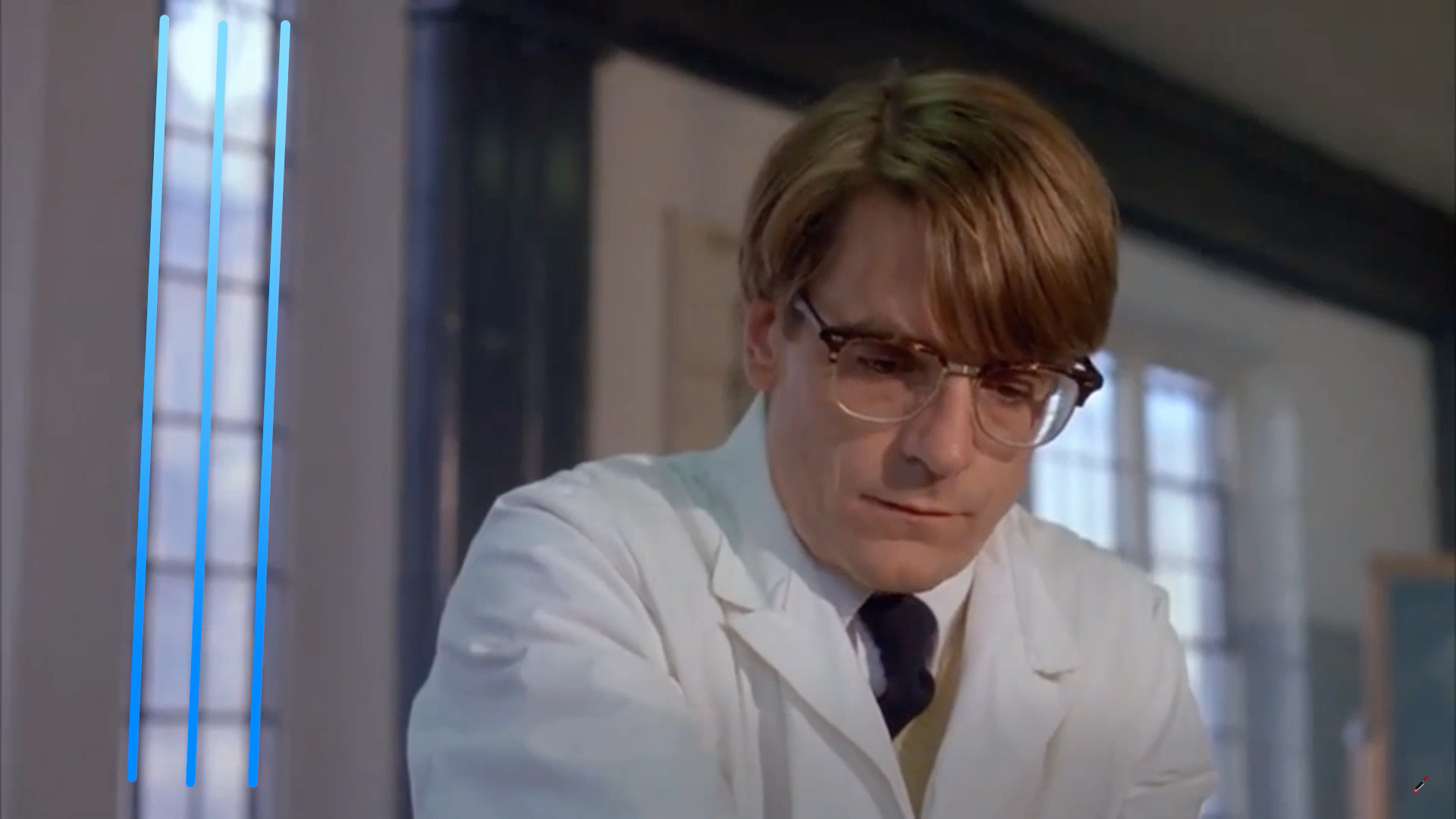

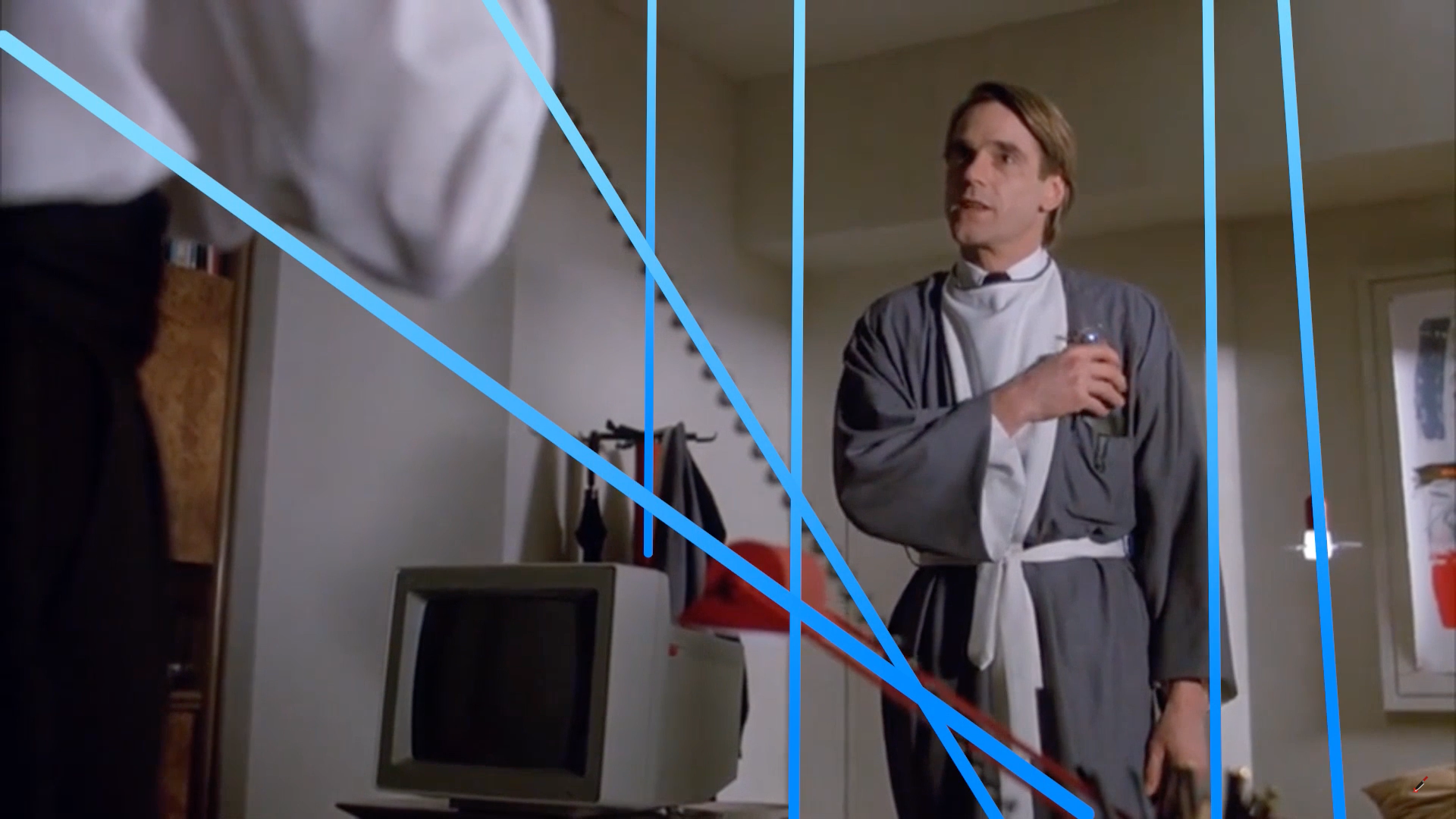

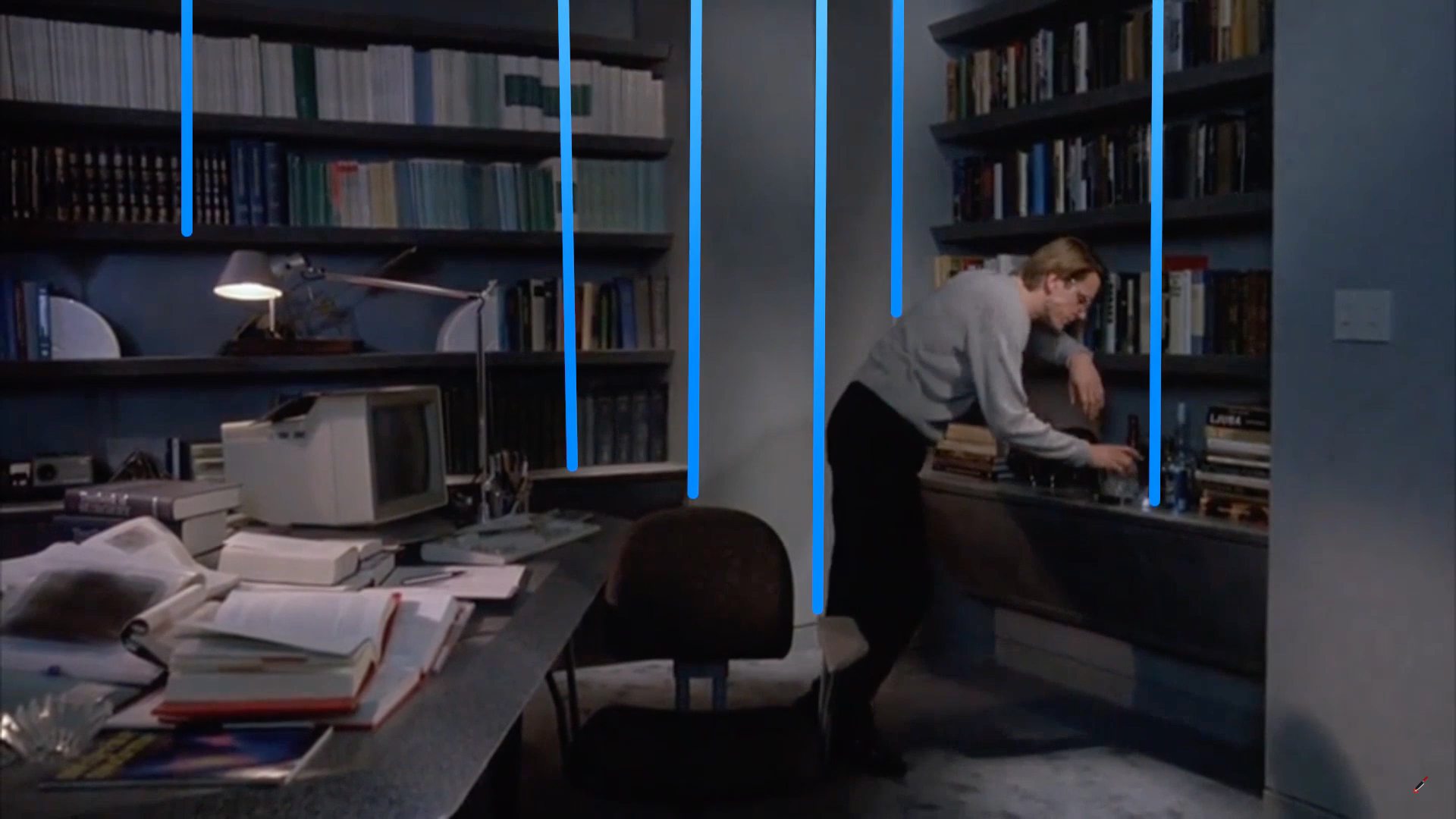

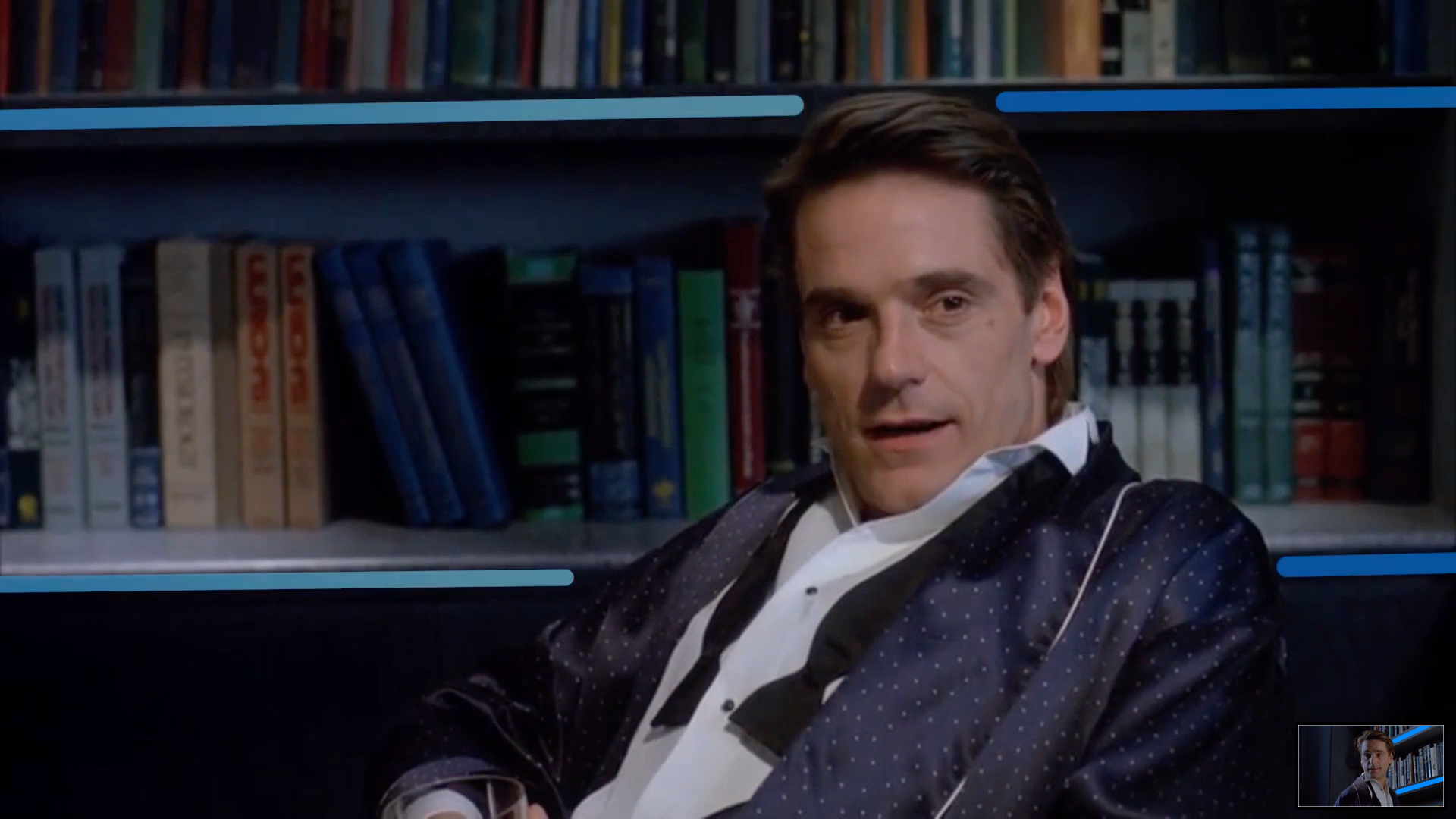

The fact is that Cronenberg sometimes uses lines so often in the frame as a visual subtext that at times it can seem like abuse. Nevertheless, in his execution, this visual emphasis looks more appropriate than ever. Let's break down the "Dead Ringers" (1988), which tells the story of two brothers who can't exist without each other, as an example. Separately, their lives are ruined, but together they cannot be free. This is how they exist in interdependence. This motif is metaphorically revealed by the bars that appear throughout the film. These can be the bars on hospital windows or doors, the abstraction created by the intersections of lines, or trivially by light.

As the story progresses, Cronenberg increasingly alienates the characters, including on a visual level. When the brothers' invention is a success and the medical community, all congratulations and regalia are taken over by only one of the brothers, Eliot. At this time, Beverly is left sitting alone in his office (note the bars on the window behind the protagonist).

In another scene, the visual contrast between the brothers is clearly visible. Shy and cramped, Beverly seems to be constrained by vertical and horizontal lines. He has no space to do anything, just as he has no chance of receiving acceptance from his brother. Eliot, on the other hand, is set against a background of purely horizontal lines, which here symbolize success and stability. And this pattern can be discerned throughout the film.

Afterword

Cronenberg is a director of contrasts. He loves to subvert the audience's expectations and has been doing so since the beginning of his career. Although we have been able to recognize a favorite pattern of personality deconstruction in his films, we are never quite sure what to expect from the maestro. For example, the first 40 minutes of The Fly unfolds like a romantic comedy and almost nothing anticipates the horror to come. Cronenberg belongs to the type of writer who can change vectors abruptly and still make stunning films (whatever the critics may say). That's probably why you, as a viewer, find yourself in awe-inspiring suspense every time you see a David Cronenberg film. We wish you a speedy introduction to the filmography of this classic and that's the end of it. Thank you for being with us today and until next week!